Collegiate scrapbooks are no longer a thing. Sure, modern students still take photographs to document their college years—arguably, they take even more than my generation, thanks to digital cameras–but instead of pasting images into memory books, they post them to Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook. It’s interesting to compare the ephemerality of today’s memory-keeping activities to the materiality of yesterday’s.

Physical scrapbooks fascinate me. I’m a scrapbooker, myself, have been since middle school, when my parents gave me my first scrapbook. It’s a traditional one, with heavy-weight paper leaves and leather-like covers bound by a cord. I still have it, tucked away in a closet. In college, I used those awful magnetic photo albums so popular in the ‘80s; they were great for speed because you just slapped down your photos and ticket stubs and other precious mementos and BOOM, you had a scrapbook. By grad school, I was into more sophisticated methods and used acid free papers and stickers and albums. The late ‘90s witnessed a sudden explosion of scrapbooking activity. Those were the days of scrapping companies like Creative Memories and Memory Makers, scrapping cruises and craft shows, web-based scrapping stores that sold high-end designer products, and independent stores that hosted scrapping classes at night. With my meager stipend, I was only on the margins of this trend. It was expensive. It was time-consuming. It was the turn of the 21st century, and people felt compelled to preserve their recent pasts as the millennium neared.

A social and cultural historian of the 19thC US, I knew how modern scrapbooking built on older forms of memory-making activities like commonplace books, carte de visite albums, clippings folders, diaries, baby books, and photo albums, as well as samplers, album quilts, crazy quilts, and so on. Scholars have written hundreds of essays and books about this phenomenon and why women did it. And it is important to acknowledge that memory-keepers have tended to be women, for whom handiwork served as an especially meaningful way to document not only important, life-altering experiences, but life-sustaining relationships.

The literature on scrapbooking, both popular and scholarly, was on my mind as I began to study alumni scrapbooks. JMU has a growing collection; the majority of them date from between 1915 and 1950, the era of the institution’s founding as a State Normal and Industrial School for Women, its growth as the State Teacher’s College, and its development as Madison College. The scrapbooks fit into a larger JMU campus history project I’ve been pursuing; my work also aligns with the Universities Studying Slavery project housed at UVa and the #campushistories effort spearheaded by folks at the National Council for Public History (NCPH). Certainly, I’m using the scrapbooks as crucial sources regarding students’ everyday lives. Informal and deeply personal, they offer an authentic counter-narrative to the official institutional accounts found in authorized, published sources like yearbooks, bulletins, and anniversary books (Young). More intriguing, I’m attracted to the way student scrapbooks functioned simultaneously as “autobiographical statements” (Buckler and Leeper) on the one hand, and as vehicles for collective identity and memory formation, on the other. As a record of a student’s collegiate years, a time of significant personal transformation, each scrapbook offers insight into its creator’s unique experiences and the meaning she attached to them. But each woman also participated in experiences common to every student on campus, from classes and dorm rules to school songs, school traditions, and local hang-outs. Then there is the way collegiate scrapbooks were made and used. It’s an obvious point, but here it is: students made them on campus, likely in the company of friends. Did they have “scrapbooking parties” like modern women? That I don’t know. Yet. But it’s clear that students purchased mass-produced college memory books locally and filled them with photos and memorabilia collected during the course of daily life. Candid shots of leisure activities dominate the photos. But the photos are secondary to the “stuff” of college: class schedules and grades, event programs, student handbooks, scraps of corsage ribbon, bits of brown wrapping paper from packages, paper napkins from picnics, and foil candy wrappers. By looking for patterns across the collection, I am learning more about the common identity they forged as white, Southern, college-educated women.

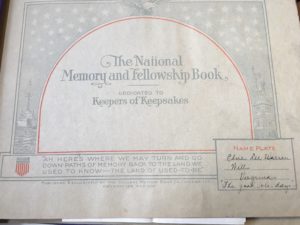

Colophon page for Elsie Lee Warren Witt scrapbook, showing its publication information. Note that she added “The good old days” to her nameplate.

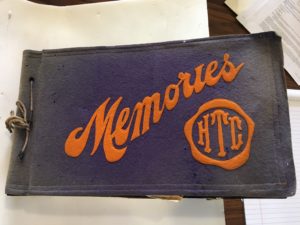

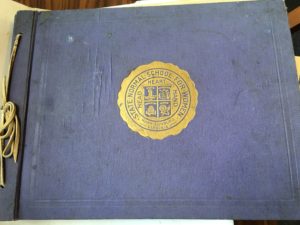

All of the scrapbooks I’ve examined to date were mass produced for the collegiate market. Sold as blank books, they contain heavy weight paper pages bound between different kinds of specially commissioned covers. The cardboard cover of Elsie Warren’s scrapbook, which she started in the fall of 1923, has purple paper with an embossed, gold seal of the State Normal School for Women, Harrisonburg, Virginia. The colophon page indicates that hers is a “National Memory and Fellowship Book” manufactured by The College Memory Book Company of Chicago, and the end papers inside depict the seals of nearly 100 other institutions for which covers could be purchased. Other scrapbooks from the 1920s have covers of purple felt stitched directly onto the first and last pages. These are marked with a gold felt applique of the word ‘Memories’ and a stylized seal with ‘H.T.C.’ for Harrisonburg Teacher’s College. Inez Graybeal’s scrapbook, by contrast, has a generic collegiate cover that bears the image of a golden plaque with the words, ‘Leaves of Yesterday. Freshman, Sophomore, Junior, Senior.’ The variety of options suggests that even the cover made a statement.

Scrapbooks could easily be found in local stores in the college’s host community. Businesses that catered to students advertised their collegiate wares in places where they could not be missed—the back pages of student newspapers, yearbooks, handbooks, and catalogs. The earliest one I have found so far is an ad in the 1895 Illio, the yearbook of the University of Illinois at Champagn-Urbana. In it, the Strauch Photo Craft House insisted that “College Memory Books are worthwhile. We supply the books, events pictures, and Kodak prints to fill it.” The Hanson-Holden Company, a stationery and book store in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, advertised its memory books in the local newspaper, saying, “Get your book at the beginning of the school year.” Here in Harrisonburg, there were two possibilities: the Valley Book Store, which sold “Everything for college students, pennants, pillows, stationery, books and novelties”; and the Nicholas Book Store, which sold “High Class Stationery, Nice Line of Souvenirs, Books of all Kinds,” and urged “College Girls . . . to make our store their headquarters.” These businesses knew their customers’ needs well. Elsie Warren was so excited when her scrapbook arrived from the Valley Book Store that she pasted a scrap of its wrapping paper into it (the part with her dormitory address) and wrote the date followed by three exclamation marks.

Page from Inez Graybeal’s scrapbook with photos and ephemera pasted over the standardized title. The facing page, titled Sophomore, is similarly covered, as are other pages.

Inez Graybeal’s scrapbook, compiled over the two years she attended, suggests how individuals personalized mass-produced albums. On the first page, clearly marked ‘Freshman’ and intended for that year’s mementos, she pasted over the title to gain much needed room for ephemera, some of which are now missing. Over the months, she added material to different pages, often pasting over other titles as she went; this act of bricolage suggests her unwillingness, perhaps, to let someone else define or limit her record of her experience. At some point, she pasted her 1931-32 student handbook onto the blank page that precedes her scrapbook’s “Freshman” page. A small booklet containing essential rules and policies, its well-thumbed cover and odd placement (it is the only item on that page) suggests she added it after her freshman year had ended and she no longer needed it.

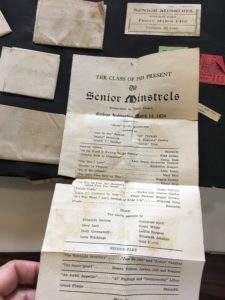

As I indicated, alumni scrapbooks not only serve as “autobiographical statements” of individual students’ experiences, but they reveal patterns of behavior, especially when examined as a collection. In particular, they affirm a point I made in a previous post, that students here actively participated in the production and reproduction of Confederate heritage, Lost Cause nostalgia, and white supremacy. Page after page after page, the scrapbooks prove how much students at this institution reveled in blackface minstrelsy, for example. They staged annual shows, attended their friends’ performances, invited male troupes from UVa and VMI to perform here, and pasted the programs into their scrapbooks to enjoy later.

As I indicated, alumni scrapbooks not only serve as “autobiographical statements” of individual students’ experiences, but they reveal patterns of behavior, especially when examined as a collection. In particular, they affirm a point I made in a previous post, that students here actively participated in the production and reproduction of Confederate heritage, Lost Cause nostalgia, and white supremacy. Page after page after page, the scrapbooks prove how much students at this institution reveled in blackface minstrelsy, for example. They staged annual shows, attended their friends’ performances, invited male troupes from UVa and VMI to perform here, and pasted the programs into their scrapbooks to enjoy later.

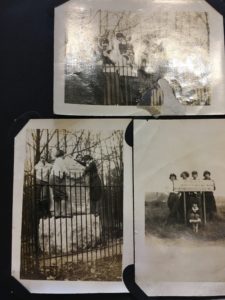

Photos of students on a trip to the Turner Ashby monument near campus. It was erected by the local chapter of the United Daughters of the confederacy in 1898, and was a regular field trip site for students at the Normal from 1909 through the 1950s.

Similarly, when they went on field trips to local Confederate monuments and battlefields, they photographed themselves at each location and saved mementos of the day like lunch napkins and leaves from nearby bushes.

Among the most interesting finds are materials from student clubs, especially the Lee Literary Society. Established in 1909, the club’s stated purpose according to student handbooks was to promote “literary activities” and “foster the ideas that were embodied in the person of General Robert E. Lee.” However, membership appears to have been by invitation only. There was also a secret initiation ceremony involving blackface minstrelsy.

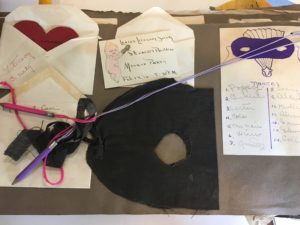

Inez Graybeal’s scrapbook preserves multiple items related to her initiation. On April 21, 1933, she received a letter from the society’s secretary, Dorothy Williams, informing her that she had been invited to join–providing she had a C in English and a C overall–and that she needed to let Williams know her decision. Another letter, dated April 24, told Graybeal that she would be “informally presented” to the members that night; it directed her to come to Harrison Hall at 6:30pm prepared to tell something of Lee’s life and to know the society’s colors, song, and motto. “This is to be kept absolutely secret,” it said. But a third note, undated, commanded her to appear “behind the practice house” (now Varner Hall) at 7:00pm dressed in “Any old costume that will make you look like an old ni**er mammy. Blacken your face and plait your hair in 13 plaits. Wear shoes and hose that you will not be afraid of ruining . . . bring a large spoon and pan . . . clothe yourself sufficiently to keep yourself warm.” It also told her to bring material “for a blindfold” and one dollar initiation fee. Though she did not record what happened, Graybeal saved all three letters, neatly folded in their original envelopes, along with a ribbon, two silver crosses, and a place card.

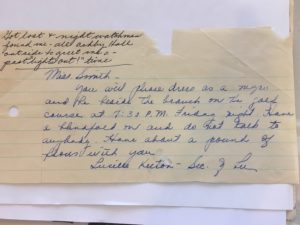

Letter from Smith scrapbook. This scrapbook was disassembled in the 1990s and items placed in acid free folders.

Graybeal was not the only student to participate in this ritual. Other students preserved their initiation invitations, too, suggesting it was an important shared memory for Lee Society members. In Miss Smith’s case, which took place during the 1940s, the mammy costume seemed intended to denigrate the initiate: when Smith “got lost” and returned to her dormitory with the night watchman well after “lights’ out,” “all Ashby Hall” turned out to “greet” her. Evidently, someone who knew where she had gone and why alerted her hall mates. Did they line the porch to watch her arrival? Did they jeer or cheer? We don’t know. That she annotated her letter with the story suggests she did not feel embarrassed or ashamed to be seen by her fellow students in blackface. To the contrary, dressing “as a negro” was not only a common occurrence on campus, but a valued, memorable part of the Normal’s collegiate culture. That’s what made it scrapbook material.

Sources Cited:

Patricia Buckler and C. Kay Leeper, “An Antebellum Woman’s Scrapbook as Autobiographical Composition,” Journal of American Culture,” 40 (Autumn 1995): 1-8.

Juliana M. Kuipers, “Scrapbooks: Intrinsic Value and Material Culture,” Journal of Archival Organization, 2:3, 89-91.

Nanci A. Young, “Educate a Girl? You Might as Well attempt to Educate a Cat!,” Journal of Archival Organization, 1:2, 53-64.