The idea for a building for alumnae emerged in 1920 as President Samuel Page Duke considered the needs of a growing campus. He became president in August 1919, as the first World War and global pandemic were still winding down and disruptions persisted. The Harrisonburg Normal School (formerly the State Normal and Industrial School for Women at Harrisonburg), which had closed temporarily during the pandemic, was bursting again with new students. The young women came from all over Virginia, eager to gain the kinds of skills and knowledge needed to join the workforce, which desperately sought women workers to replace men in all kinds of fields. Duke need funds for everything: dormitories, classrooms, offices, and even the social spaces so necessary for student life. The Alumnae Association quickly stepped in to help raise money.

Continue readingAuthor Archives: Meg

Yuri Nemoto: Madison’s First Asian American Student

A few years ago, I purchased a 1944 School Ma’am in a local antique store and was astounded to find inside two photographs of an Asian American Madison College student named Yuri Nemoto. A quick search of The Breeze turned up a brief 1943 interview that refers to her as the “first” student “of Japanese descent,” which means she is likely the first Asian American. Nemoto told the reporter, an unidentified fellow classmate, that she was from Los Angeles, had come to Virginia on a scholarship to Lynchburg College, and transferred to Madison that fall intending to study dietetics. Well. I had so many questions after reading that. How had she not been sent to a detention camp along with more than 110,000 to 120,000 other people of Japanese ancestry? What had it been like for her to be a Japanese American attending a whites-only Southern school during World War II? My research revealed a compelling story of resistance and resilience.

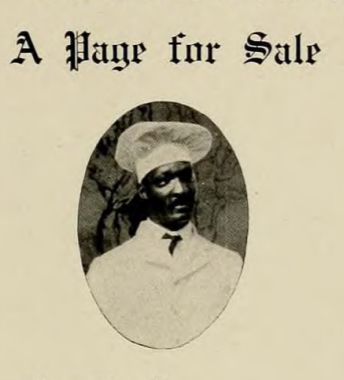

Continue readingPage S. Mitchell, Chef and Kitchen Manager

Page Mitchell was one of the most significant employees at the State Normal and Industrial School for Women, for he managed the kitchen that provided three meals a day to hundreds of white students and faculty. Hired as the school’s cook, he is shown in a 1914 image, at left, in chef’s whites. Like Walker Lee and the handful of other African Americans that worked on this campus in the early 20th century, Mitchell contributed to the school’s success, however, little information about him survives in school sources. In this post, I’ll piece together what I have learned about his work so far.

Continue readingSheary Darcus: JMU’s 1st Black Graduate in Context

In April 2020, The Madison Magazine, JMU’s alumni publication, featured Dr. Sheary Darcus Johnson, whom the institution recognizes as its first African American graduate. I provided some important historical context for that cover story and reproduce my sidebar here, followed by an update related to other early Black students. [read more]

Continue readingStudent Orgs, the Lost Cause, and Belongingness

NB: I started this post in 2019 but completed/updated it in response to JMU’s July 2020 decision to remove the names of Confederate officers from campus buildings. This post references historic examples of racist and oppressive imagery and language.

In 2019, some Kappa Alpha brothers from Ole Miss made headlines when they used Emmett Till’s memorial marker for target practice and reignited old debates about fraternities and other student orgs that invoke the Lost Cause. The Kappa Alpha Order, a fraternity established in 1865 at Washington College in Virginia, claims Confederate General Robert E. Lee as its “spiritual founder,” and is widely recognized by historians for its veneration of the Old South and its particular brand of white, Southern masculinity. Lee became their icon because he served as president of that college from 1865 to his death in 1870, when campus authorities renamed it Washington and Lee. KA chapters expanded over time, and by the 1950s and 1960s, were widely known for hosting elaborate “plantation” parties, flying Confederate flags, and actively opposing efforts to desegregate higher education. (Turner, Coski) JMU’s KA chapter dates to the 1994-95 academic year, when opposition to affirmative action admissions was nationally prominent, and this campus, like many others, struggled over its diversity initiatives (Breeze, 1990-2000). This post connects modern JMU student organizations’ Lost Cause activities to earlier forms, like the Lee Literary Society, and reflects on their impact on white and Black student belongingness and campus culture. [read more]

Continue readingPandemic at the Normal, 1918

Everyone wants to draw lessons from the past right now. My Twitter TL is full of links to news articles comparing the COVID-19 crisis and the 1918 influenza pandemic. There’s even a #COVID19syllabus project that gathers recent articles and supplements them with scholarly books and articles. So I couldn’t ignore the fact that my campus closed in 1918, just as it closed in March 2020. Sitting in Webex meetings with other administrators, I wondered what happened back then, what decisions those administrators made, and what impact influenza had had on the State Normal School at Harrisonburg. [read more]

Continue readingAuthor Talk, “Black Powder, White Lace: The Irish Community at Hagley”

In 2014, I gave an invited lecture at Hagley Museum and Library, the nation’s leading center for the history of business and technology. The topic was based on my 2002 book, Black Powder, White Lace: the du Pont Irish and Cultural Identity in 19th Century America. A videorecording can be found here: https://www.hagley.org/librarynews/video-black-powder-white-lace-du-pont-irish-and-cultural-identity-nineteenth-century

Ethical Reasoning in Action

In this 2015 video, I make the case for The Madison Collaborative: Ethical Reasoning in Action, JMU’s Quality Enhancement Plan, which I co-created.

4

Civic Engagement Award

In this 2017 video, I summarize JMU’s approach to Engagement, for which JMU received the AASCU Excellence and Innovation Award.

3

In the Past Lane: interview

In this 2018 podcast, Rethinking and Remembering: The 1898 Wilmington, NC Massacre and Coup, I talk with Ed O’Donnell about my book, Race, Place, and Memory: Deep Currents in Wilmington, NC. In the 1990s, I was involved in a public history initiative to commemorate the centennial of the massacre and coup. As O’Donnell says, my work “stirred a lot of controversy because it challenged the convenient cover story for what happened in November 1898 by demonstrating that it was a naked and calculated act of white supremacist political violence.That experience prompted Mulrooney to write Race, Place, and Memory to examine the long sweep of the city’s history to reveal many incidents of white supremacist violence, both before and after 1898, that were either forgotten or misremembered. It’s both a history of a representative southern city and a consideration of the role of public history in fostering an accurate vision of the past and insights into the challenges facing American society in the present.”