NB: I started this post in 2019 but completed/updated it in response to JMU’s July 2020 decision to remove the names of Confederate officers from campus buildings. This post references historic examples of racist and oppressive imagery and language.

In 2019, some Kappa Alpha brothers from Ole Miss made headlines when they used Emmett Till’s memorial marker for target practice and reignited old debates about fraternities and other student orgs that invoke the Lost Cause. The Kappa Alpha Order, a fraternity established in 1865 at Washington College in Virginia, claims Confederate General Robert E. Lee as its “spiritual founder,” and is widely recognized by historians for its veneration of the Old South and its particular brand of white, Southern masculinity. Lee became their icon because he served as president of that college from 1865 to his death in 1870, when campus authorities renamed it Washington and Lee. KA chapters expanded over time, and by the 1950s and 1960s, were widely known for hosting elaborate “plantation” parties, flying Confederate flags, and actively opposing efforts to desegregate higher education. (Turner, Coski) JMU’s KA chapter dates to the 1994-95 academic year, when opposition to affirmative action admissions was nationally prominent, and this campus, like many others, struggled over its diversity initiatives (Breeze, 1990-2000). This post connects modern JMU student organizations’ Lost Cause activities to earlier forms, like the Lee Literary Society, and reflects on their impact on white and Black student belongingness and campus culture. [read more]

In the September 4, 1995 issue of The Breeze, the new fraternity’s secretary explained that the members sought to “bring chivalry and knighthood to JMU.” Fall rush was just about to start, and the new chapter needed members. He said KA was founded in 1865 and that the fraternity “considers Confederate General Robert. E. Lee to be its spiritual founder.” According to other copies of the Breeze and the Bluestone, which have been digitized, a small group of white JMU students had investigated the fraternity and received permission to establish a provisional chapter in January 1994; they received their charter in April 1995, when 37 members were inducted formally. (The month of January has historically been associated with Lee-Jackson birthday observances, and April with Confederate memorial events.) The Bluestone yearbook for the 1995-6 academic year suggests the scope of KA’s success: it featured a full page recognizing the new chapter with names and photos and text describing KA’s values of “chivalry, honor, respect for God, women, and gentlemanly conduct.”

Mike Ingram, class of 1996, recently wrote about his experiences as a founding member of JMU’s KA order: “The chapter I joined at James Madison University never celebrated Old South, and I never saw any Confederate flags. Most of my fraternity brothers were from the D.C. suburbs or points farther north. But we had the requisite oil painting of Lee in our house, and I couldn’t pretend to be wholly ignorant of KA’s national reputation.” It’s worth a read, as this excerpt indicates:

Several years ago, I was talking to my then-girlfriend about my fraternity days. By then I’d developed a set of stock answers to the inevitable questions. Yes, the Lee thing was problematic, but no one in our chapter took it seriously, and anyway it wasn’t really about the Civil War, or even the South. “It was about being gentlemen,” I said. “You know, chivalry and all that.”

The look she gave me: I can still see it. Maybe I should mention that she was working on a PhD in history; she’s now a professor. “You realize those things are all connected,” she said. “The whole cult of Lee, and chivalry and knighthood, and the Civil War as this noble lost cause?”

I don’t remember what I said then. I probably hemmed and hawed for a while, or tried to change the subject with a dumb joke. Eventually I must have admitted she was right, because of course, she was. But college had been a long time ago. I was only a kid. Who could possibly care anymore?

Then Charlottesville happened.

https://humanparts.medium.com/how-i-confronted-the-truth-about-my-fraternitys-racist-history-2202e05ec08a

Lee remained a publicly prominent aspect of the fraternity’s identity throughout the 1990s. The 1998 and 1999 Bluestone yearbooks both feature a full page on KA with various members’ photos and names. The accompanying text reads, in part, “Originally organized to show respect for Robert E. Lee, the brothers of the local chapter worked to uphold Lee’s ideals. As the ‘gentleman’s’ fraternity, members were always respectful of others.” In other posts, I’ve shown how yearbooks, scrapbooks, and other student-made sources are important windows into campus values. They prove that veneration for the Lost Cause and its white, patriarchal icons, including Lee, was woven deeply into the fabric of this institution’s curriculum and culture in the early 20thC, just as it was on campuses across the United States. But it is still jarring to see these legacies perpetuated into the contemporary era.

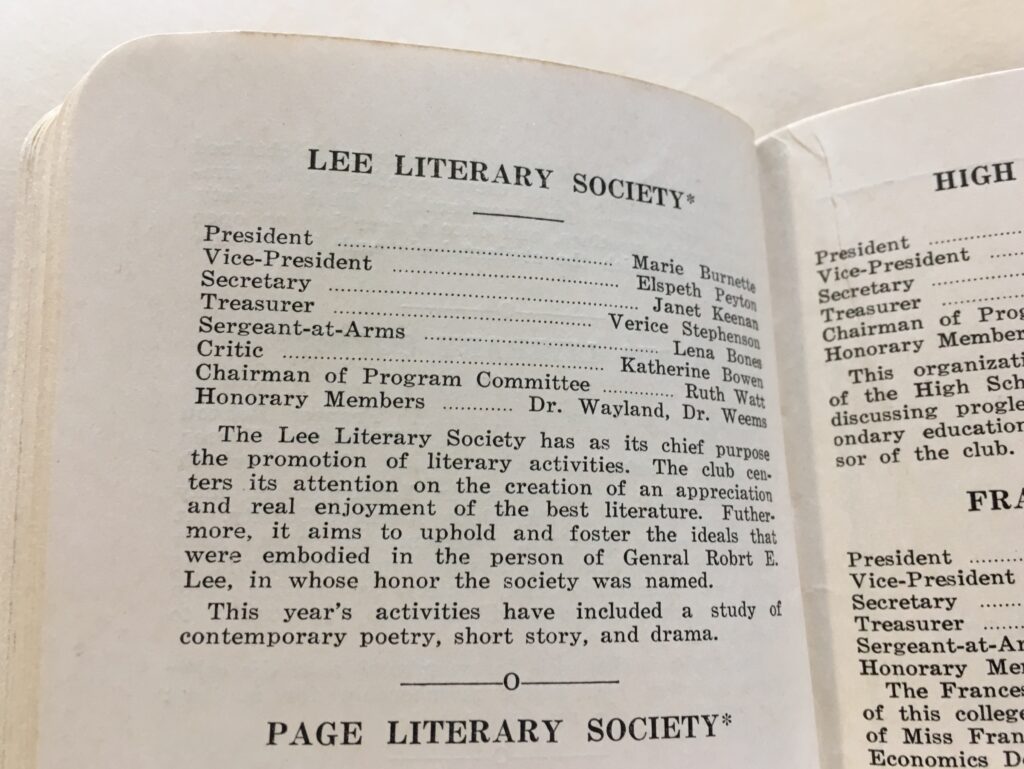

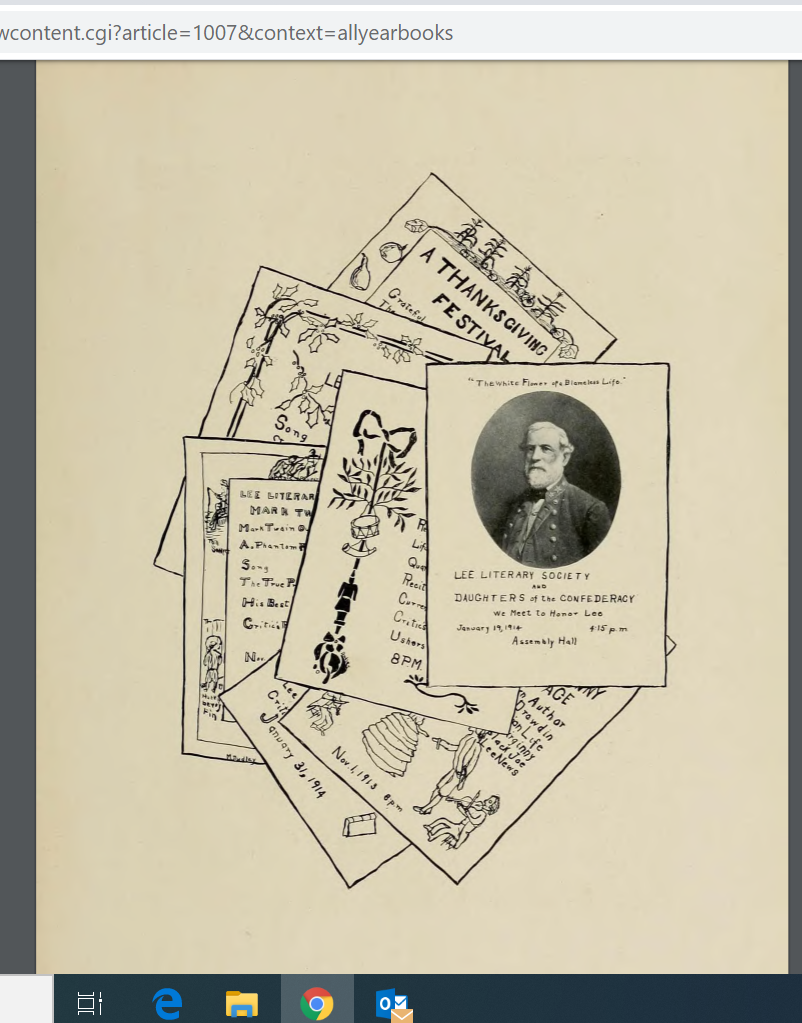

Interest in Lee as an icon of both the “Old South” and the Lost Cause can be traced back on this campus to its very first semester, when Dr. John Wayland and students established the Lee Literary Society in 1909. David Gold and Catherine Hobbs have analyzed the function of literary societies at white, Southern, women’s schools in the Progressive era; they argue that these student orgs, like the women’s schools themselves, simultaneously reinforced racial hierarchies while undermining gender conventions. Like women students elsewhere, members of the Lee Society focused on developing skills in research, writing, rhetoric, and debate that were intended to prepare them for public speaking, broadly, in expectation of their emerging place in the public sphere. Yet the content of their writing and speaking centered on the Lost Cause mythology.

For Gold and Hobbs (as well as scholars like Amy McCandless and others), this Janus-like blend of forward-looking/progressive/New South notions of education and social change AND backwards-looking/regressive/Old South nostalgia for the days of slavery and patriarchy is what made white women’s colleges so distinctive. White women had new opportunities, true, but they still needed to be Southern ladies, always deferential to white male authority. These “competing tropes” not only characterized other student orgs, but every other aspect of this segregated institution, from the administrative structure to the curriculum. And that explains why gendered, racialized memories of the Old South recur here through the decades: they were normalized as part of campus and student identity.

Just a few examples suffice to show persistence over time. By the 1940s, the Lee Literary Society had been disbanded. However, the Old South and Lost Cause remained visible at Madison College in blackface minstrel shows, May Day pageants, field trips to local Confederate historic sites, and UDC-approved textbooks. (A fascinating 1950s marketing video for Madison College shows the ongoing tensions between modernity and nostalgia: see a student in the Stratford Drama Club “blacking up” at 16:18 and May Day pageant at 16:40.) Importantly, the post-war decades saw the increasing presence at Madison of white men students, who, though they could not live on campus, nevertheless participated actively in student culture. Someday, I hope to write a post about the relationship between the cult of the Old South and the parallel cult of Old England (Anglo-Saxons-Middle Ages-Shakespeare-May Day), but I expect readers will see how the 1947 adoption of “the Dukes” by the men’s basketball team was an homage to white, male, chivalric culture (akin to UVa’s Cavaliers).

Despite the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education, Madison College followed the rest of the state in massively resisting federal desegregation orders. President G. Tyler Miller (a VMI alum) apparently supported the state’s 1955 plan to use public funds for private, all-white schools (DNR 1/6/55) rather than comply. Although there is evidence that a woman of mixed race graduated from Madison in 1958, the institution continued publicly to uphold statewide segregation policy throughout the civil rights era. In fact, Madison’s admission of two heroic African American women in 1966, managed under Virginia’s “freedom of choice plan,” was part of an intentional stalling tactic, one used across the South. (Lassiter et al; Grundman) During the civil rights era of the 1950s-1970s, symbols of the Confederacy’s Lost Cause gained new power in Virginia as white opponents of desegregation cast their battle as yet another fight for “state’s rights” against a federal tyranny. (Coski)

In the early 1970s, overt Confederate iconography and hagiography on this campus rose again along with the population of white men and fraternities. President Carrier began his administration in 1971 with an aggressive push for both co-education and desegregation. By the end of 1972, the number of white men had increased from about 25% (1100) to 35% (1500) and the number of Black students (men and women) to 72. Student yearbooks show the normalized display of Confederate symbols at Madison: 1973 Bluestone captures members of the Alpha Chi fraternity unabashedly flying the Confederate battle flag, while the 1979 issue documents a male student in pseudo-Confederate garb in the homecoming parade. This resurgence occurred on many campuses and was part of national cultural shift in the 1970s that historian Bruce Shulman calls ‘southernization.’ It can also been seen in the strong interest at Madison in Southern rock and bluegrass. Similar examples recur throughout the 1980s, as well, as when an unidentified group held a dinner “celebrating the birthday of Confederate cavalry commander Turner Ashby” and invited Confederate reenactors to fire a cannon outside Gibbons Dining Hall as part of the event. (Breeze, Oct. 25, 1987) This long tradition helps explain how a new fraternity came to organize around Robert E. Lee in 1994 and why its membership grew into the 2000s.

By far the most visible, enduring symbols of the Lost Cause tradition on this campus are the buildings named in 1917 for Confederate officers Maury, Jackson, and Ashby, although the Board of Visitors voted on July 7, 2020, to remove those names and begin a process of renaming them. Many campuses have pursued renaming strategies because they finally recognize the incongruity between these memorials and modern institutional values. Yet the movement to rename or remove these symbols isn’t new, not even at JMU. In 1992, an Asian-American SGA senator, Franklin Dam, proposed a resolution to change the names of Ashby and Jackson halls, arguing that “some of the principles behind the Confederate states are offensive.” Though it didn’t pass, Dam’s proposal proves that the racist ideologies associated with the Lost Cause were being publicly opposed here in the 1990s, even as KA was being imagined. As I perused the Breeze recently, I found similar evidence, going back to the 1970s, that other students, especially Black ones, had consistently called out racist iconography and traditions. What happened is that, with the inception of new, anti-racist icons and traditions like the annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Day march and speak out (established 1977) and related programming sponsored by Black fraternities, sororities, and student organizations, the campus became a contested terrain for collective memory. Yet these contests didn’t occur on a level playing field. On a predominantly white campus, white perspectives predominate.

In Race, Place, and Memory (2018), I explained why places have great power: people form attachments to buildings, spaces, cities because, as physical, tangible environments for human behavior, they both reflect and shape our sense of belonging to (or alienation from) a spatially-bounded community. A college campus similarly “shapes and continues to shape the sense of belonging and dignity of its students.” (Alderman and Rose-Redwood) This is why the movement to rename campus buildings and remove public symbols of racism has gained momentum. Non-white or BIPOC college students and their allies have grown in number since the early 2000s, following national demographic shifts. As one study argues, “although a campus, as a racialized memorial landscape, can certainly be a place of exclusion, it can also be a site for . . . an ‘oppositional politics of belonging’. The very presence of discrimination can be the source of its potential undoing and hence the university’s geography of naming and remembering can become a site where marginalized groups can lay claim to the campus and struggle to create a more inclusive and multicultural setting. [emphasis added]” (Brasher, Alderman, Inwood)

But battles over named buildings, statues, flags, and other Confederate icons also reflect a specific reckoning with historicism, the belief that it’s possible to understand the past as it actually was, as if the interpretations contained in monuments, books, or paintings depict the reality of the past. Statements related to “erasing history” or owning it (“it’s our heritage”) reflect this antiquated sort of historicist thinking. And it is very common because that is how history classes have long been taught in K-12 schools (and colleges, too). The new historicism, however, recognizes history as an ongoing process, rather than a fixed product. In this view, shared by most professional, credentialed historians, we welcome the constant arrival of new facts, new sources, new methods, and new questions that lead inevitably to new interpretations. Revising and correcting past knowledge is standard practice on a college campus; it’s why ALL faculty conduct research, publish, and teach new findings in the classroom, regardless of academic discipline. And revising and correcting one’s self-knowledge is also important.

In his essay, Ingram recounts his personal reckoning with historicism as well as racism. He describes school field trips to plantations and textbooks that advanced Lost Cause versions of US history, for example. Historicism intersected with other -isms in the simplified, romanticized figure of Robert E. Lee, Kappa Alpha’s “spiritual leader.” [W]hite supremacy was embedded in the lessons I learned in school, and in the aristocratic power structures of old-money Charleston, and in the willful ignorance I practiced every time I tried to shrug away my fraternity’s ugly history,” he wrote. His analysis of the way KA at JMU replicated “aristocratic power structures” and the gendered and religious aspects of Old South-Lost Cause iconography feels timely because recently reinvigorated contests over campus statues, monuments, and buildings are part of a broader reckoning with not only the racism that lingers in higher education, but the classism, sexism, and faithism. Fraternities and similar kinds of student orgs, including the old Lee Literary Society, aren’t open access, after all; through a selective initiation process, they signal who belongs to what group–and who does not. Here as elsewhere, current students and alumni value the belongingness that KA membership affords. Some may wonder what all the fuss over Lee is about, while some see Lee’s “gentlemanly” ideals as a positive source of masculine self-identity and guide for living in the 21st century. Other KA brothers, however, like Ingram, have publicly renounced the brotherhood’s Lost Cause origins. The result of each person’s reflection or self-knowledge will be different.

I’m committed to antiracist work and to diversity, access, and inclusion efforts at JMU because, as an educator, I know people can and do change as they learn from others around them. Still, “isms” learned in youth can leave their mark despite an adult’s best efforts. Implicit biases and blind spots are a very real, very powerful phenomenon for everyone, me included. I have used this blog, my classes, invitations to lecture publicly, and committee service to share accurate information about JMU’s history and to help myself and other administrators confront institutional biases and systems that continue to affect the present. One of those institutional biases is seen in the long tradition of favoring Lost Cause iconography and prioritizing the belongingness of white students and alumni over the belongingness of BIPOC students and alumni. In July 2020, JMU turned a important page on that history.