This building commemorates noted 19th century scientist and oceanographer Matthew Fontaine Maury, who resigned his commission in the US Navy in 1861 to serve as a commodore in the Confederate navy. After the Civil War, he briefly lived in Mexico, where he tried to create a slaveholding colony for exiled Confederates. He eventually returned to his home state, Virginia, and accepted a position as professor of meteorology at Virginia Military Institute. A strong advocate for public higher education, he helped create the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Virginia Tech). Photo by author.

I’m republishing this May 2017 post today 6/20/20 with a disclaimer: it contains references to historic ideas, words, and images that today are considered racist. I temporarily removed it because links to it were circulating on mass media and social media, and portions of it were taken out of context.

Talk of Confederate heritage seems to be everywhere these days. As a public historian who studies, teaches, and writes about this subject, I find the sudden resurgence fascinating and repellent at the same time. Mitch Landrieu, the mayor of New Orleans, put it well when he said, Confederate statues “are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.” I make a similar point in my forthcoming book, Race, Place, and Memory: Deep Currents in WiImington, NC, which includes an analysis of monuments and memorials in that city. But my interest is more than academic. Every day, I go to work in a building that long served as a Confederate monument. To be clear, my views on renaming/removing/contextualizing such monuments are still evolving—I take no position, not yet. Since few people at JMU know the history of this campus, I offer this post as a starting point for others interested in this topic. My study of this institution’s past is very much a work in progress, and I hope to offer additional information later.

The Lost Cause on Bluestone Hill

Built in 1909, Maury Hall opened just in time to welcome the first class of students enrolled at the State Normal and Industrial School for Women. At that time, the building was called Science Hall and it was the sole academic structure: it held the president’s office, the library, the bookstore, and all of the classrooms. Many of the students came here to become teachers and partake of an innovative curriculum designed to meet a shared standard or ‘norm’. The only other buildings of note at the Normal were a dormitory, which housed a student dining room in the basement and a modest second-floor apartment for the president and his family, and a former farmhouse that accommodated the female faculty.

These buildings were seated on a gentle rise just south of the town of Harrisonburg. The architect, Charles Robinson, stipulated construction with local limestone, a distinctively dark, blue-gray rock that soon gave rise to the campus nickname “Bluestone Hill.” With their white, classical elements and red tile roofs, the structures had an unusual yet striking appearance. As enrollment grew, additional dormitories followed.

“Bluestone Hill” as it appeared ca. 1915. From left to right: Science Hall (Maury), Dormitory 1 (Jackson) and Dormitory 2 (Ashby). JMU Special Collections.

In 1917 the trustees of the Normal approved a recommendation from a faculty member to rename its academic buildings for Confederate heroes. Science Hall was renamed in honor of Matthew Fontaine Maury, a Virginia-born scientist (the “Father of Oceanography” or “Pathfinder of the Seas”) and commander in the Confederate Navy. His biographer John Grady notes that Maury was a controversial figure while alive, but by this date, thanks especially to his daughter’s 1888 memoir, he had become widely romanticized as a “great benefactor if his race.” Similarly, the original dormitory became Jackson Hall in recognition of Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, the Confederate general who led the 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, and a second dormitory became Ashby Hall in honor of a local Confederate cavalry officer, Turner Ashby, of nearby Port Republic. Together, these structures memorialized not only the specific deeds of these three men, but a particular interpretation of the Civil War—an interpretation that the faculty and administration expected the future teachers to pass on to Virginia schoolchildren.

In a paper called “White and Black and Bluestone: Racing History at the Normal, at Madison, and Beyond,” I explored the emergence of a distinct Bluestone identity that reinforced white privilege by inculcating respect for traditional southern womanhood, pride in Virginia’s unique past, and reverence for the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. Well known to historians, the Lost Cause ideology held that the south had only lost the Civil War because of inadequate manpower: The Confederate cause was just, white southerners were virtuous people, and slavery was a benign institution that benefited an inferior, black race. Like David Gold, who has studied the Lost Cause at several southern women’s colleges, I found at the Normal a strong desire to honor the local Confederate heritage of the Shenandoah Valley as well as that of Virginia and the south, broadly. Campus buildings played a critical role in this effort because of their fixity and permanence. Even so, a pro-Confederate, profoundly racialized attitude informed almost every aspect of daily life at the Normal–from the curriculum to the school song and planned excursions to local battlefields.

The Curriculum

The curriculum offered the most obvious way to promote the Lost Cause, and it did so on multiple levels. Textbooks, for example, became increasingly race conscious during the early 20th century. Fearful of the sudden influx of Eastern and Southern European and Asian immigrants, American textbook authors celebrated the contributions of early settlers from “native stock,” a term meaning chiefly the English but also Germans, Scots, Scot-Irish, Dutch, and sometimes French settlers (but only Protestant Huguenots). These filiopietistic narratives reflected broader shifts in the instruction of history, which under the so-called Progressive school became more “usable,” more practical and civics-oriented, and less academic. At southern colleges, administrators and faculty made an overt effort to link the popular cult of the Anglo-Saxon to the south’s distinctive racial system and culture and thereby restore regional pride.

Operating on a quarter system, the Normal offered a four year high school diploma, plus several two-year, post-secondary, professional tracks. These prepared students for certification as kindergarten, elementary, or high school teachers. All students on the professional track were required to take courses in six core subjects: English, Math, Geography, History and Social Sciences, Foreign Languages, and Natural Sciences. Early bulletins provide course titles, descriptions, and lists of required textbooks.

Within the core subject History-Social Sciences, Normal students had limited options set by the faculty. Each student had to take a two-quarter integrated sequence in ancient, medieval, and modern European history (which only included France and Germany). They also took one quarter of English History, a quarter of US History methods, and one quarter of US History. In the US content course, the emphasis was “industrial, economic, and political progress,” and the assigned texts were John Fiske, US History for Schools (Houghton Mifflin,1895) and Edward Channing and Albert Bushnell Hart, Guide to American History. Fiske’s book was one of the most popular texts in this era: it went through thirteen editions!

A well known public intellectual, Fiske taught philosophy and history at Harvard and was a devotee of Herbert Spencer, whose ideas about the eventual decline of non-white races he spread through his own writing and speaking engagements. While scientific racism did not characterize his textbook, which was geared toward children, his prose did privilege the white perspective in its treatment of actions taken against enslaved persons, freedmen, Native Americans, and Chinese immigrants.

Channing had a similar approach. Also a professor of history at Harvard, he helped develop the idea of an “American” race as a new category. In his works, English colonists were the most important because they contributed so much of the nation’s language, culture, customs, and laws, but he acknowledged other Anglo-Saxons, too, who by “process of assimilation” strengthened the “American” breed. The Guide was a useful companion to the Fiske text because it was a reference work designed to serve the needs of primary and secondary teachers. It listed various topics, offered a summary, and followed each one with a bibliography. Note that these cursory texts did not serve the history methods course, but the content course. At the Normal, all “subjects were taught from the standpoint of the student being able to teach them, rather than from merely acquiring knowledge.” Apparently, the faculty didn’t want to tax the students’ female minds too much.

Virginia history was a popular elective. Here, the text was Mary Turner Magill’s History of Virginia for Use in Schools, first published 1881 and extensively reprinted. Magill lived in Winchester, VA, where she and her mother ran a private school after the war. The women were very successful in attracting pupils because they capitalized on their close,personal relationship to Stonewall Jackson. Magill, described by a Winchester historian as a “fierce Confederate,” dedicated fully one-third of her 374 page book to a certain four year period, with the Shenandoah campaign of 1862 receiving its very own chapter. Her goal, simply stated in the preface, was to give Virginia’s children “a record so full of honor … that they may well be proud of it.”

Dr. John Wayland and students gathered at the New Market battlefield in 1912. This site appears to be part of the Bushong farm, where in 1864 teen-aged cadets from the Virginia Military Institute slogged through a field so muddy that it sucked the shoes off their feet. Although many cadets died, the charge succeeded and helped Confederate troops secure a victory that day. JMU Special Collections.

All of these books were chosen by Dr. John Wayland, who directed the history curriculum at the Normal until 1931. A Shenandoah Valley native, he received his doctorate from UVa in 1907 and eventually authored more than thirty books that mainly focused on local and state history. In keeping with his German heritage, his work especially celebrated the German immigrants who helped settle the Virginia backcountry, but he also acknowledged the English and Scots-Irish. A highly influential figure, for whom another dormitory was later named, Wayland also chaired the excursions committee.

Dr. Wayland and students on a 1910 excursion to the Turner Ashby monument. As pilgrimages to sacred sites associated with the Lost Cause, these field trips served an important didactic purpose but they were also opportunities to socialize and build school identity. To commemorate them, Wayland often arranged formally staged photographs that appeared in early yearbooks and personal scrapbooks. JMU Special Collections.

Bulletins and faculty minutes indicate the didactic function of these field trips. Each year, Wayland took students to the “hallowed site where the gallant Ashby fell in 1862” (a monument near the campus), as well as the spot “where the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe crossed Blue Ridge in 1716” (Swift Run Gap). Other popular nearby destinations were the “old home of Abe Lincoln’s ancestors,” which nodded toward the national reconciliation project, and “the place where young Daniel Boone spent a year of his life,” which echoed efforts to celebrate early settlers. Confederate battlefields, however, were paramount, especially Cross Keys, “where Jackson won an important victory” and the so-called “field of lost shoes” at New Market battlefield.

Student Organizations and Activities.

Like other Normal schools in Virginia, Harrisonburg’s offered students myriad opportunities to socialize. The young women had a German Club, an Arts Club, and a Kindergarten Club, just to name a few. Most organizations had a clear co-curricular function. The Shakespearean theater troupe, for example, reinforced required courses in literature and English History and celebrated an idealized Anglo-Saxon heritage. Similarly, the Normal boasted two literary societies, which students established in the very first quarter session. They named one for Confederate veteran and poet Sidney Lanier, who once spent six weeks at a resort near Harrisonburg, where he wrote one of his early volumes. The other, however, honored General Robert E. Lee.

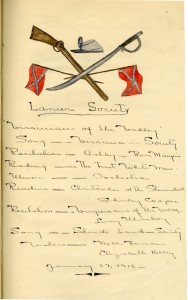

Hand-lettered and illustrated program for a Lanier Literary Society event in 1918. Besides the Confederate emblems, note the content. JMU Special Collections.

Both literary societies decorated their posters, programs, and yearbook pages with Confederate symbols like battle flags, kepis, and cavalry swords. Beginning in 1910, the Lee Society joined the local chapter of the United Daughters of Confederacy (UDC) for annual receptions. On January 19,1913, the anniversary of Lee’s birth, the ladies of the UDC presented an actual Confederate battle flag to the Normal, care of the Lee Society. To honor the courage and sanctity of Lee was, of course, to honor the courage and sanctity of his “country,” Virginia, the students’ home state. Thus, in 1918 the Lee Society published a special, inspirational poem called “The Spirit of Lee;” it appeared in the yearbook beneath a photo of the famous “Recumbent Lee” memorial sculpture at Washington & Lee and expressly connected Virginia’s call to arms in 1861 to the nation’s call in World War I.

Another popular Lost Cause activity bears noting: each year, the Virginia Military Academy cadets re-enacted a march made in 1864, when a group of young cadets walked from Lexington to New Market, where they aided a stunning Confederate victory in 1864. As the cadets passed the campus, the Normal’s female students lined the main road to wave and cheer them on. (The re-enactment of the march remains a famous custom for modern VMI cadets.) In the Progressive-era reenactments, cadets assumed the role of heroic defenders, while Normal students played their loyal, protected ladies.

An image from the 1917 yearbook, The School Ma’am, showing the Senior Minstrels dressed for one of their skits. JMU Special Collections.

Other activities, like minstrel shows, proclaimed Normal students’ attitudes about white supremacy/black inferiority. The 1917 yearbook featured a multi-page spread on the Senior Minstrels. That year, a group of black-faced white women, some of whom played black men, staged a skit called “A Dark Night at the Normal.” The four featured characters, Sambo, Tambo, Bones, and Fitznoodle, also offered a variety of musical performances as part of the show. Significantly, the young women were invited to perform at the Virginia Theater downtown at a community-wide Lee celebration on January 19 and again on campus on January 22. The following year, the Junior class staged a ‘vaudeville’ featuring a performance by two women in blackface. It was part of a larger skit called “The Booster Club of Blackville.” Characters featured included “Abraham Lincoln Washington, running after chickens,” and “Alexander Thicklips, pork chop inspector.” Minstrelsy deeply permeated popular culture in this era. As scholars like Grace Elizabeth Hale have shown, in consuming caricatured images of blackness, Americans became more self-consciously white. What’s important to note here is that these students were not merely consuming—they were actively creating minstrel shows which they proudly performed and to which they attached their own names and identities. And minstrel shows remained popular on Bluestone Hill through the 1950s, as yearbooks attest.

Beyond the Normal

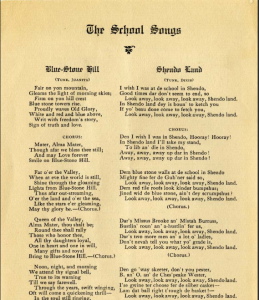

The Normal had two school songs: the official one, Bluestone Hill, and the unofficial one, Shendo Land. Written by Dr. John Wayland and set to the tune of Dixie, Shendo Land was fondly remembered by students, who sang it for many decades.Commencement program, 1912, JMU Special Collections.

As I’ve indicated, this study is very much a work in progress. Like other scholars of American higher education, I’m especially interested in how administrators and faculty (past and present) shape an institution’s racial climate by what they explicitly promote and tacitly allow to occur on campus. In the early decades of the 20th century, the Normal’s president, Julian Ashby Burruss, its Board of Trustees, and faculty like John Wayland shared a common sensibility that they promoted among their female students through curriculum, student organizations, and even the physical structures. And the women students were not passive recipients of their Bluestone identity. They actively participated in its construction. While there are indications that some pushed back, alumni records indicate that most students then seemed to understand and embrace the Lost Cause and its racialized and gendered hierarchies. Consider that the school’s official alma mater until 1931 was “Bluestone Hill,” but students preferred the unofficial one, called “Shendo Land.” Sung to the tune of Dixie and written in a racist dialect, it began: “Oh, I wish I was at de school in Shendo/ Good times dar don’t seem to end, so/ look away, look away, look away, Shendo Land/.” Together, five verses gently satirize strict rules regarding male “beaux,” the bluestone buildings with their “bumptious” red tile roofs, and the faculty, while celebrating the absence of mosquitos, the noise of the railroads, and the swish of a basketball. I’m still not entirely sure what to make of their ditty, but it clearly seems a form of cultural inversion–through ridicule, the song worked to affirm their racialized, gendered identity and to ground it a specific geographic place. Their complicity is important to recognize because nearly 500 women had graduated by 1920 and several thousand more after that. From the Normal to Madison College, alumni took their certificates and their Bluestone identity with them as they fanned out across the state, teaching generations of white children who became generations of white parents.

Selected Secondary Sources

Dingledine, Raymond. Madison College, 1908-1958.

Frost, Dan R. Thinking Confederates: Academia and the Idea of Progress in the new South.

Gold, David. Students Writing Race at Southern Public Women’s Colleges.” History of Education Quarterly, 50, no. 2 (May 2010): 184-203.

Graves, Karen. Girls Schooling in the Progressive Era.

Hale, Grace. Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South.

McCandless, Amy. The Past in the Present: Women’s Higher Education in the Twentieth Century American South.

Moreau, Joseph. Schoolbook Nation: Conflicts over American History Textbooks from the Civil War to the Present.

Riley, Karen. “Fair and tender ladies v. Jim Crow,” American Educational History Journal, vol 37, issue 1/2 (Sp 2010): 407-417.

Stronger, Patricia A. and Irene Thompson, eds.. Stepping Off the Pedestal: Academic Women in the South.