In April 2020, The Madison Magazine, JMU’s alumni publication, featured Dr. Sheary Darcus Johnson, whom the institution recognizes as its first African American graduate. I provided some important historical context for that cover story and reproduce my sidebar here, followed by an update related to other early Black students. [read more]

Dr. Johnson’s positive memories of Madison College reflect her unique experiences in the 1960s. Placed in historical context, her story reminds us that JMU’s campus was once segregated, and that thousands of Black Virginians were denied equal access to education. Many Americans mistakenly think that the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 ended racially separate schools. In fact, southern states quickly implemented a policy of “massive resistance,” the term coined by the movement’s leader, Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd. Since the U. S. Supreme Court’s ruling allowed localities to determine the process for and speed of desegregation, some communities in Virginia, dominated by pro-segregation whites, decided to close their public schools rather than comply with federal mandates, while others explored strategies for limited desegregation. Lawyers for the NAACP, Oliver Hill and Spotswood Robinson, continued to sue uncooperative school boards in an effort to achieve substantive change. During Johnson’s childhood, Harrisonburg garnered significant statewide attention. The Friendly City was one of a handful of white-dominated localities that voted against a controversial Virginia constitution amendment to redirect public school funds to private, all-white, charter schools; it also boasted Madison College, the state’s leading teacher-training institution as well as the District Court for the Western District of Virginia federal courthouse, where in 1956 and 1958 Judge John Paul issued two pivotal rulings that contradicted the Byrd machine’s directives. But despite local support for desegregation, Harrisonburg schools remained racially separate until 1964, when Dr. Johnson and ten other individuals formally desegregated the high school, now JMU’s Memorial Hall.

Johnson’s admission to Harrisonburg High School and later, Madison College occurred under so-called freedom of choice plans. These plans emerged after the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which allowed the federal government to sue noncompliant school districts and withhold federal funds. On paper, freedom of choice plans allowed families to choose which schools they wanted their children assigned to, but in practice, they functioned as yet another way to preserve dual school systems. In Virginia, no white families switched to Black schools, and the number of Black families that, like the Darcuses, requested and actually received reassignment was very small. Thanks to additional NAACP suits, the U. S. Supreme Court declared freedom of choice plans unconstitutional in Green v. New Kent County, VA (1968). By that time, Madison College had admitted just a few Black students. Although Dr. Johnson is Madison’s first African American graduate, preliminary research suggests there were possibly two individuals who attended before her but kept their racial identity concealed. There is still so much to learn as we study Madison’s complex past.

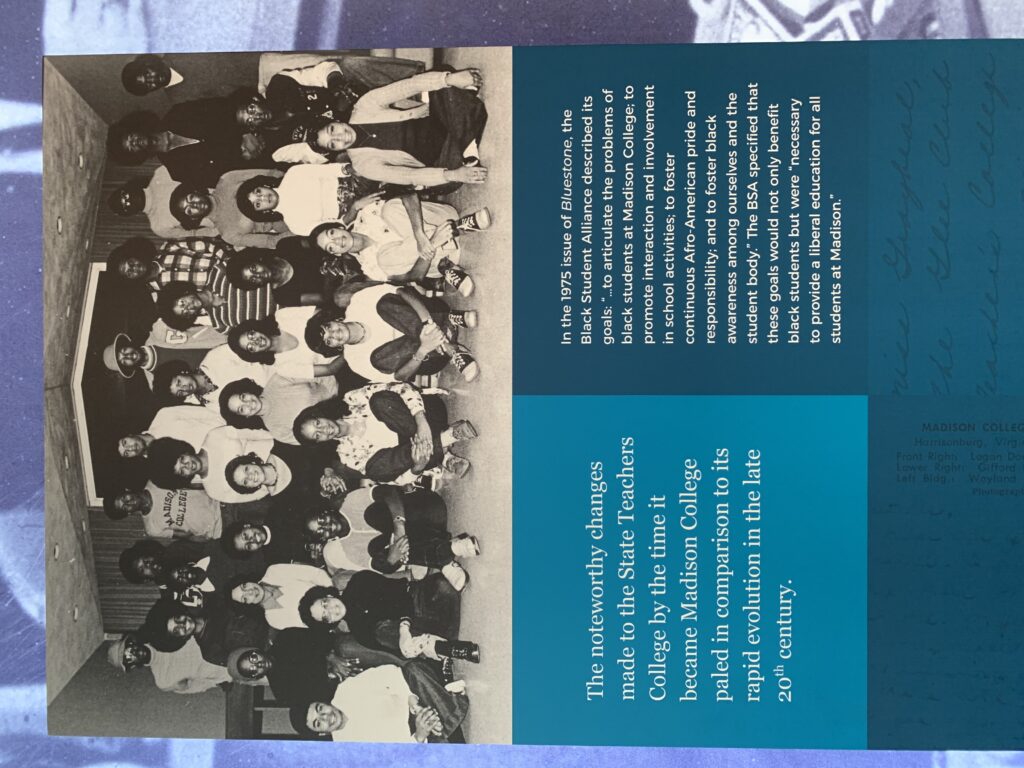

Desegregation efforts expanded under President Ronald E. Carrier, who began his tenure in 1971 determined to transform the institution from a single-sex, segregated college into a comprehensive university. By 1972, Madison enrolled 72 Black undergraduates out of a population of 5,000. The establishment of Delta Sigma Theta in 1971, the Black Student Alliance in 1972, and new courses in African American history after 1975 demonstrated a new commitment to change. So did the hiring of Black faculty and staff. After Governor John Dalton finally settled the last federal suit against Virginia in 1978, integration at the newly-christened James Madison University accelerated.

Before JMU recognized Dr. Johnson as the first graduate, marketing personnel claimed her as the first Black student. I find the idea of labeling anyone a “first” understandable but very problematic; there has never been an official institutional archives on campus, so what Trouillot calls the “silences and mentions” in what does survive in Special Collections need careful, scholarly assessment. In an oral interview, for example, a Black woman who worked as a domestic at Madison in the 1950s names a student who the woman strongly believed to “have Negro blood.” It takes time to trace such stories in the historical record, and while the supporting evidence is strong, there are also anomalies to address. There is also the ethical question of contacting persons or descendants of persons who may have hidden their identity. It is certain, however, that another African American woman also enrolled at Madison in 1966. She is mentioned by Darcus Johnson herself in a 2019 Breeze article. Apparently, this woman lived on campus in a dormitory and faced enough harassment from white women that she withdrew. Who was she? Would she even want to be recognized, to tell her own story? Darcus Johnson consistently credits her individual merit and choice (“It was meant to be.”), even as she acknowledges that others had different experiences. Such narratives are common in American culture, reflecting an older, master narrative of success that supports the American Dream. What about the Black women who enrolled in 1968, including Saranna Tucker, Sandra Johnson, Janis Smith, and Juanita Etheridge? How an institution approaches its “first” generation of Black students matters (see William and Mary’s 50th Anniversary of African Americans in Residence Project for a good example). Alumni relations are typically tied to fundraising and marketing offices, not academic departments or libraries and archives. Even if select Black alumni are interviewed, recovering the administrative decisions behind their admission, the exact number, and their varied experiences is difficult without a rigorous methodology.

Sources do confirm that in 1967, Madison admitted James Rankin, Jr., and that Purcell Conway followed the next year. They may be the first Black men at Madison College, but corroboration is needed. White men had been allowed to take classes as day students starting back in the 1910s, however, they were not permitted to live on campus until 1966, which marks the start of full co-education at Madison. I don’t yet know whether a Black man enrolled in 1966. The Breeze is completely, loudly silent on the subject of racial desegregation, despite the obvious presence of at least two Black students on campus that year, yet articles referencing white men and coeducation are frequent.

Scholars have thoroughly documented overt and covert resistance to desegregation on lily-white, southern campuses. Women’s colleges were not exempt from the kinds of hostility and violence we associate with historically men’s institutions like Ole Miss or the University of Georgia; perhaps sexist images of “genteel southern ladies” distort our understanding of the transition at places like Madison. [Williamson-Lott, Sokol] Consider why Black students lobbied for a Black Student Alliance in 1969, for example. They sought recognition (through establishing a funded, formal student org) of the need for peer-based support for the 30-35 persons faced with integrating a campus of roughly 3,500 white students. (Breeze Feb. 18, 1975) Specifically, the BSA’s mission was to “articulate the problems of black students at Madison College; to promote interaction and involvement in school activities; to foster continuous Afro-American pride and responsibility; and to foster black awareness among ourselves and the student body.” (Bondurant Jones) The BSA continues to serve this role to this day.

What about graduate students? New programs were added in this period as part of a concerted effort to grow the institution. Also in 1969, Donald L. Banks graduated from Madison’s new masters’ counseling program, making him possibly the first Black graduate student. A resident of nearby Elkton, Banks worked in the college counseling center part time during the 1969-70 academic year, likely to support Black students. The 1971 Bluestone yearbook lists him as the center’s full-time director, but he left Madison soon after to pursue a doctorate. Barbara Blakey, a teacher at the recently desegregated Harrisonburg High School, enrolled in a Madison master’s program in 1971. Sheary Darcus, of course, returned for her master’s, too.

In the 1970s, the number of Black undergraduate students began to slowly rise. Dr. Carrier, inaugurated as president of Madison in 1971, encouraged limited desegregation as both a practical and personal priority. The official state policy, however, still mandated resistance, as noted above, and Governor Mills Godwin’s letters to Carrier in Special Collections document the continued directives from Richmond. Joy Williamson-Lott argues in Jim Crow Campus that presidents of southern schools faced enormous pressures to resist integration from conservative lawmakers and constituents, yet they also coveted federal funds needed to expand their campuses. Carrier seems to have been caught in this bind in the 1970s. Eager to grow Madison into a modern “multi-versity,” he greatly increased the undergraduate population, especially directing the rapid admission of white men, yet only 72 Black students were enrolled in 1972 out of about 5,000 total. Special efforts to recruit Black students included targeted marketing brochures (one produced by the BSA), minority admissions recruiters, funds for additional Black student organizations, and tours to Virginia’s predominantly Black high schools of the Madison Gospel Choir. By 1975, 1.9% (roughly 120) of the college’s 6,900 students were Black. (Breeze) The numbers would not grow much further until Gov. John Dalton finally settled the federal government’s suit against Virginia in 1978. That change resulted in the newly renamed James Madison University launching a comprehensive affirmative action plan for students.

Many Black students who attended Madison in the 1970s are now active in JMU’s alumni association. A scholarly oral history project designed to capture their memories and document their experiences would be an important way to add to our understanding of this pivotal time in JMU’s history. I hope someone takes up that task.

Sources for this post include:

Lassiter, The Moderates Dilemma

Williamson-Lott, Jim Crow Campus

The Mad ’70s, sv ‘Desegregation at Madison’

The Breeze