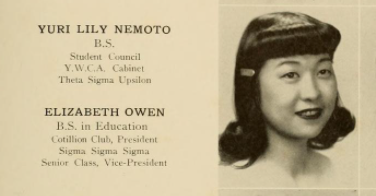

A few years ago, I purchased a 1944 School Ma’am in a local antique store and was astounded to find inside two photographs of an Asian American Madison College student named Yuri Nemoto. A quick search of The Breeze turned up a brief 1943 interview that refers to her as the “first” student “of Japanese descent,” which means she is likely the first Asian American. Nemoto told the reporter, an unidentified fellow classmate, that she was from Los Angeles, had come to Virginia on a scholarship to Lynchburg College, and transferred to Madison that fall intending to study dietetics. Well. I had so many questions after reading that. How had she not been sent to a detention camp along with more than 110,000 to 120,000 other people of Japanese ancestry? What had it been like for her to be a Japanese American attending a whites-only Southern school during World War II? My research revealed a compelling story of resistance and resilience.

It turns out that, from her first days on campus, Nemoto not only claimed a role as a highly visible student leader, but she leveraged white curiosity about her self and her family to raise awareness at Madison of the terrible conditions faced by incarcerated Japanese and Japanese Americans. And she knew these conditions first hand because, as I learned during my research, she spent at least one summer, possibly two, living with her family in the federal government’s internment camp at Rohwer, Arkansas. Her experience as this institution’s first “Asian American” student cannot be understood apart from the broader of context of the World War II era.

I offer Nemoto’s story to expand what is known about this institution’s growth and development from a whites-only women’s college into a desegregated, co-educational university. It is worth noting that she enrolled 23 years before the first Black woman, Sheary Darcus, but 17 years after the first Latina, a woman who likely would have identified as Panamanian. Following the Asian American scholar Leslie Bow, I also seek to understand “what racial identity segmentation demanded of those who seemed to stand outside or between its structural logistics.” (Bow, Partly Colored) There were, after all, many people whom whites in the segregated South labeled “colored” besides African Americans–these included Asian Americans, Native Americans, Latin Americans, and various ethnic Americans who at different points in time were considered “near white” but still experienced race prejudice. How did it feel to Nemoto to grow up in segregated Los Angeles and see her family incarcerated, then live, dine, and learn with white women every day in Virginia? Reclaiming Nemoto’s story complicates what we know about segregation in the past and informs the way we advance diversity, equity, and inclusion in the present.

Little Tokyo

Nemoto grew up on the southern edge of Los Angeles’s Little Toyko, the largest community of Japanese immigrants and their families in the United States. Federal immigration records available through Ancestry indicate that her father, Moichi Nemoto, arrived from Japan in 1904, just before the Gentlemen’s Agreement severely limited Japanese immigration. With his status listed as a student, he entered through the port of Seattle en route to San Francisco. I can’t tell when he moved to Los Angeles, but many Japanese did that after the devastating 1907 San Francisco earthquake. In the spring of 1916, he returned to Japan to collect his picture bride, Yai Tsumori, who was 14 years his junior. (He called her a picture bride in his naturalization papers.) Census schedules indicate that the couple had the first of their five daughters, Hatsu, in 1917, then Kimi in 1919 and Mitsu in 1922. When Yuri arrived in 1923, the family lived on Kohler Street near the Terminal Market, but they then moved several blocks south to Birch Street, where the youngest, Matsu Florence, was born 1926. According to her obituary, Yuri Nemoto remembered many aspects of her childhood positively, especially long drives with her parents and sisters.

Historian Valerie Matsumoto provides a vivid portrait of the community in Los Angeles that Nemoto knew. Little Tokyo, established in the 1890s, had become a vibrant Japanese cultural hub by the 1930s. Of the estimated 35,000 persons of Japanese ancestry who lived there, about half were Japanese-born Issei and about half American-born Nisei. A 1913 California state law prohibited non naturalized Japanese from purchasing property or signing long-term leases, however, many families established profitable shops and businesses, including the famed flower market at Ninth and San Pedro. Moichi Nemoto is listed in city directories as a shoe repairman with a shop at 1235 E 7th St. Unable to own and segregated through white residents’ use of restrictive covenants, the Nemotos moved around from rental to rental, but generally stayed in the same area of the city, near his shop and the Terminal Market. Yuri attended the de facto segregated Ninth Street elementary school and probably participated in one or more of the many social and cultural clubs where Nisei children studied Japanese language, dance, and sports like kendo and sumo. During the Great Depression, Americans of Japanese and Chinese ancestry were denied access to state and federal New Deal welfare programs, so she and her sisters likely held jobs to help the family make ends meet.

Matsumoto describes how the large, multi-ethnic city offered young women like the Nemoto sisters many opportunities to explore modern life and create a distinctly Japanese American urban culture. Young Nisei often felt torn between popular and parental values, however. Segregated politically and economically as well as geographically, they experienced overt racism and felt pressure to Americanize, to reject their ethnic heritage and language, yet they also wanted to honor family tradition and culture. Gender expectations for women were especially restrictive, with Issei parents expecting daughters to marry men of their parents’ choosing. Modern women who wanted to work faced great difficulties. According to Matsumoto, white collar jobs in 1930s Los Angeles were so rare they were especially coveted. After high school, Kimi Nemoto attended Los Angeles Junior College in 1938 and found employment as a secretary. Hatsu, by contrast, evidently married a Japanese man, Takamura Matsuzaki, who arrived in 1937 and worked for the Suzuki Company. Yuri’s older sisters provided important role models for her and may have shaped her determination to go to college.

Interviews with Los Angelenos of Japanese ancestry who were incarcerated in camps document the increased racism they experienced after the Sino-Japanese war began in the Pacific in 1937. Scholars argue that US media reports of atrocities committed by the Japanese army during the Nanjing Massacre that year exacerbated longstanding claims by white anti-Asian exclusionists in California that Issei and Nisei residents were members of a ‘devious,’ ‘degenerate,’ and unassimilable race. US foreign policy toward Japan also changed. In 1939, in response to the Japanese invasion of French Indochina, the US imposed strict economic sanctions on Japan, and, more ominously, President Roosevelt approved moving a large portion of the US fleet from San Diego to Honolulu and Manila. In August 1940, facing rising domestic hysteria about the possible presence of German, Italian, and Japanese infiltrators in the US, Congress passed the Alien Registration Act, the first legislation to require all non naturalized persons to register. Still, families like the Nemotos never imagined what would happen next.

Mass Removal and Incarceration

On Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise strike against US bases in the territories of Hawaii, Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines intending to prevent US military intervention in the Pacific. Aiko Hertzig-Yoshinaga, then a Los Angeles high school student like Yuri Nemoto, recalled hearing the news of the attack at Pearl Harbor and being very shocked, but not immediately worried. At school the next day, however, she began to feel the change:

I think our friends, non-Japanese friends, didn’t really know how to treat us. I think they knew that we would be hurt if they ostracized us. On the other hand, just like our neighbors who lived around us, I believe that they felt if they were too friendly with us, they would be labeled “Jap-lovers.” … We were treated with a sort of disdain.

Later that day, Dec. 8, Congress declared war on Japan. It was Yuri Nemoto’s 18th birthday.

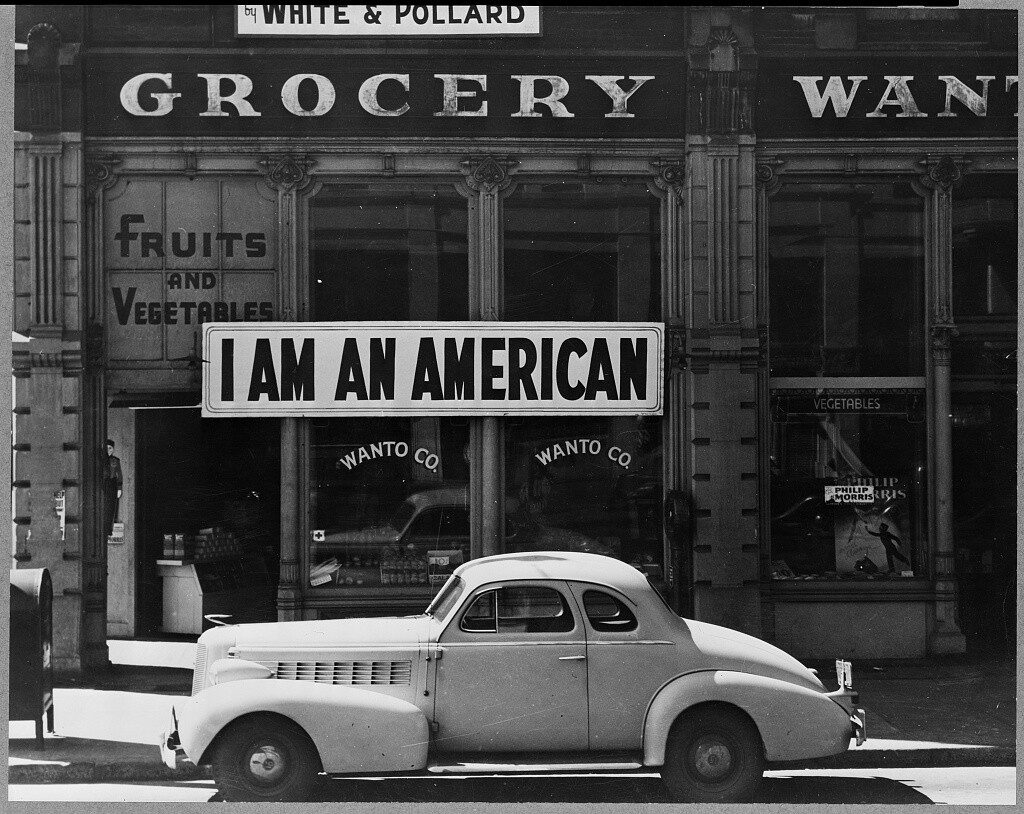

In a 2018 speech, actor George Takei remembered how quickly whites in Los Angeles, his home town, turned against the Issei and Nisei in their midst. Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, armed FBI agents aided by local police began rounding up Japanese and Japanese American professionals and businessmen. By Dec. 8, they had already taken more than 700 pre-identified “enemy aliens” into custody, and the US Treasury froze their bank accounts. City officials imposed on Japanese and Japanese American residents a 7pm to 6am curfew, and joined white employers in firing workers from their jobs. Bewildered, many Nisei tried to affirm their citizenship and demonstrate loyalty to US. They believed that, as US citizens, their constitutional rights would be upheld. Instead, prominent whites, including Mayor of Los Angeles Fletcher Bowron and California Congressman Leland Ford, called publicly for the mass removal and incarceration of all persons of Japanese ancestry living in west coast communities. On Feb. 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the secretary of war and any military commander designated by him “to prescribe military areas…from which any or all persons may be excluded.”

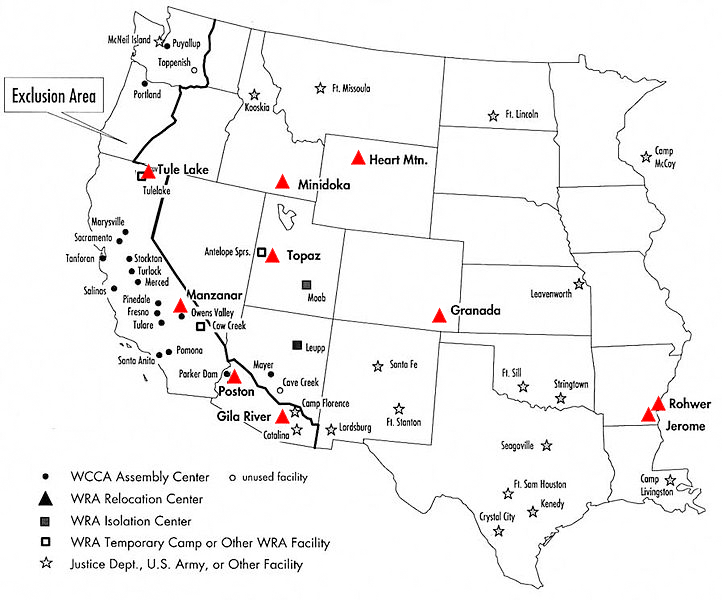

White government officials generally used euphemisms like ‘evacuation’ and ‘relocation’ to mask what actually happened, but today we use accurate terminology. Mass removal began with establishment of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) in mid-March 1942 and lasted for weeks, due to the size of Los Angeles’s Japanese population. Families like the Nemotos received ‘exclusion’ orders that told them where to report for transport to a so-called ‘assembly center’ and to bring only what they could carry. They had little time to safeguard belongings or protect businesses and investments. On April 25, 1942, sixty-five year old Moichi Nemoto presented himself at the local draft board office and registered for military service, perhaps in a last ditch effort to avoid removal. His draft card shows the family address was 927 Birch Street. The Nemotos were sent to the assembly center in Arcadia, California, about 13 miles outside city, to await ‘relocation’ further inland. Judging by their address, they were probably among the west central downtown residents removed on April 29.

The Arcadia center occupied the haphazardly converted Santa Anita racetrack grounds. There were fourteen other detention centers, where the government held incarcerated families while prison camps far away from the coast were being built. Living conditions at all of the temporary centers were deplorable, especially as the population increased. Santa Anita, the largest detention center, housed more than 18,000 people at its peak. More than 8,000 of them occupied converted horse stalls that still stank of manure. Altogether, Yuri and her family spent five months there.

While at Santa Anita, Yuri Nemoto received a scholarship to attend Lynchburg Christian College in Virginia. In her 1943 Breeze interview, she said her family belonged to the “Disciples Church” [Disciples of Christ] in Los Angeles, that members of the congregation had arranged it for her, and that she “was released” from the racetrack facility to travel east. She had taken classes at UCLA that fall and may have welcomed the opportunity to continue her studies, but it must have been an agonizing decision to leave her family behind. Somehow, probably by taking a combination of trains and buses, she traveled from California to Lynchburg, Virginia, arriving in time for classes to start in September 1942.

In the segregated Jim Crow South, Asians and Asian Americans occupied an unusual in-between status as “honorary whites.” As Bow explains, this designation meant a Nisei woman like Nemoto could sit in the white sections of buses and theaters, use white-only restrooms and drinking fountains, and attend a white-only college. It didn’t mean that whites in Virginia treated her as an equal. White faculty and students at the small, private Lynchburg College, established by the Disciples in 1903, may or may not have been welcoming of the Japanese American stranger in their midst. All we know is that Nemoto wanted to study dietetics, and since Lynchburg didn’t have that program, she resolved to transfer. How she learned about Madison College and received admission from President Samuel Page Duke’s administration is unknown at this time. Given the heightened scrutiny of Japanese Americans and the specific circumstances of Nemoto’s scholarship, it is likely that her application required special permission.

Rohwer Concentration Camp

I was stunned to learn that, after her freshman year at Lynchburg concluded, Nemoto traveled west to Rohwer, Arkansas, to spend the summer 1943 with her family. A camp newsletter, The Rohwer Transmitter, announced her presence along with several other “visiting” guests, so it’s clear that she wasn’t staying long. Today, there is nothing left of the Rohwer camp except the cemetery. When she arrived, however, it was a large, intimidating 500-acre prison complex located in swampy southeast Arkansas, far from any sizeable population centers. Actor George Takei, known for his role as Mr. Sulu in Star Trek, has vivid memories of his long train journey to Rohwer, the barbed wire that surrounded the camp, and the sentry tower that loomed over the gate. The Nemotos, classified as family 12875, were admitted Oct. 7, 1942. There were 36 bunkhouse blocks, each containing twelve rough, wood and tar paper barracks. Digitized records indicate that the Nemotos were assigned two areas inside bunkhouse 11. Moichi and Yai Nemoto occupied space D along with daughter Mitsu. Daughters Kimi and Matsu were assigned to F.

The Densho Encyclopedia offers a succinct overview of the Rowher camp and its unique characteristics, such as its unusual location in the Jim Crow south. A 1943 report on the camp’s first year, called The Pen and produced by the detainees, provides many details, but it was a censored document and cannot convey the difficulties and trauma the residents endured. The Pen noted there were “8,464 residents in the tarpapered barracks” at the start of the year, but that the number had declined to 6,706 by date of publication [p25]. According to federal WRA policy, detainees were only to be held temporarily until they could be ‘relocated’ to places elsewhere in the US. The reality was very different, as many scholars have proven. Nevertheless, the report documents the process and encouraged incarcerated persons to present themselves to the Rohwer relocation office to learn about work release options. In addition to securing outside employment, residents could get approval to enlist in the armed services or attend college somewhere. Leaving the camp, however, brought a different set of problems, including the guilt of leaving family behind and immersion in overwhelmingly white, often hostile communities. Records show that Kimi Nemoto, formerly a secretary, was assigned work at Rohwer as a teacher and as a telegraph operator. Kimi is also listed as the Rohwer Federated Christian Church’s recording secretary. She applied for work release and eventually secured a job in Kansas City, Missouri. Yuri once again found her own means of escape, this time bound for Madison College in Harrisonburg, VA.

Madison College

Yuri Nemoto arrived at Madison in September 1943 to begin coursework in dietetics. She may have developed this interest at UCLA or at Lynchburg. Wartime demands encouraged many American women to pursue occupations in nursing and adjacent health professions. Madison had a strong dietetics program that dated back to the institution’s first decade. In 1943, however, the Madison Bulletin notes the program was called Foods and Nutrition; it was a concentration available while pursuing a BS in Institutional Management. All of her required chemistry, dietetics, and cooking classes were held in what was then called Maury Science Hall (currently Gabbin Hall). The building was a short walk from her room in Sheldon, a dorm reserved for second year students. She would have also crossed the Quad to take meals in the dining hall on the third floor of Harrison Hall, which is also the building where she picked up mail from her family in Rohwer. Though the only Asian American on Madison’s campus, Nemoto’s experiences at UCLA and at Lynchburg may have helped prepare her for the challenge of living with hundreds of white Southern women.

Evidence from campus sources suggests how Nemoto not only acclimated to life at Madison, but became a recognized leader. Significantly, her name first appears in print in The Breeze on Friday, Sept. 17, 1943, as the little sister assigned to Maxine Duggar, vice president of the college’s YWCA and already an ordained minister. The YWCA was among the most important student organizations, and its annual Big Sister-Little Sister program, started in 1909, required that each new student be paired immediately and publicly with an older one who agreed to serve as a kind of mentor and help “in getting adjusted to campus life.” A junior, Duggar was in charge of making the assignments and may have chosen Nemoto for herself from among the roughly 200 freshmen. She would have known that Nemoto was a transfer from Lynchburg College and a member of the Disciples Church. Nemoto’s religious faith afforded her an entree into the overwhelmingly Protestant campus that she would not have had if her parents remained Shinto or Buddhist. In the first week, Nemoto attended a YWCA party for all the big-little sister pairs, YWCA vespers (held in Wilson Hall every Friday), and a reception at the President’s house, Hillcrest, where she would have met President Duke, his wife, and many faculty. Everyone would have taken note of the first Japanese American student.

The initial interview Nemoto gave to The Breeze on October 1, 1943, sparked invitations to address student groups on the subject of Japanese incarceration. She gave her first formal talk to the YWCA in mid-October, then another to the members of Sigma Phi Lambda in November. It’s not hard to imagine the way she had to navigate the politics of anti-Asian racism with a white audience. In her Breeze interview, she carefully noted, for example, that “internment” was “for purposes of safety to the country as well as safety to ourselves.” Her words appeared in quotation marks, suggesting that either she or the reporter wanted to make sure readers knew the words reflected her own views. Nemoto could have declined to speak publicly at all, but instead, she persisted in her efforts to educate the campus. She intentionally joined the International Relations Club (IRC), as well. The IRC was known that year for the frequency of “discussions that turned into debates” as Madison students tried to understand the United States’ role in the global war.

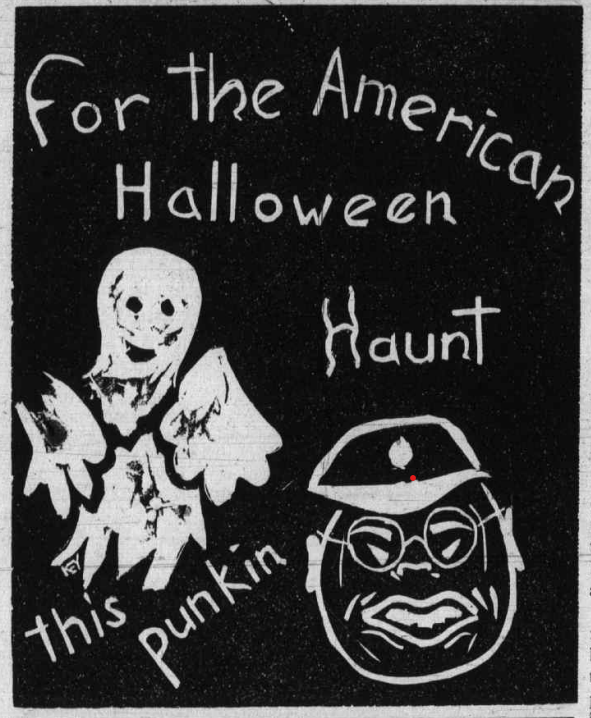

There isn’t much evidence of overt anti-Japanese behavior at Madison, but campus publications were heavily censored even in peacetime. One clear indication of local attitudes is a cartoon-like linoprint image that appeared in The Breeze on Oct. 29, 1943. It features a smiling ghost hovering over a disembodied Japanese soldier’s head with the words “For the American Halloween haunt this punkin.” A general pro-American/anti-Axis powers attitude pervaded everything at Madison during the war years. There was a Campus Defense Council led by Mrs. Bernice Varner, Dean of Women, a victory garden located behind the library, campaigns to buy war bonds, bandage rolling parties, and a regular column in The Breeze that summarized news about “Japs” and “Nazis.” When Madison’s white women students went to see movies at the Virginia Theater on Main Street, they saw propagandistic news reels that uniformly represented people of Japanese ancestry as violent, primitive, and “cunning.” In this climate, whites who routinely enjoyed anti-Black minstrel shows, Old South-themed dances, and other racist activities at Madison in the 1940s surely displayed prejudice toward Asian Americans, even as they interacted with Nemoto. She very likely encountered what we call microaggressions all the time, but she may have experienced more direct forms of anti-Asian racism and discrimination, too, such as name-calling, vandalism of personal items, grade deflation, or worse.

Nemoto continued her educational campaign into her junior year. In the fall of 1944 she organized for the YWCA a special program focused on world fellowship and for the International Relations Club (IRC) a film series in which members discussed the lives of individuals in places like the Congo and western China. When evaluated as a group, her activities are connected by the broad theme of human similarity, instead of difference. This theme was undoubtedly evident in a January 1945 talk she gave to the IRC on “Japanese and Japanese Americans in the US.” According to The Breeze, Nemoto “made known to the members present many facts concerning the mass evacuation of 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry” and “gave information about boys of Japanese ancestry serving in the armed forces.” By that time, she was President of the IRC, an officer in the Frances Sale Club for home economics and dietetics majors, and a member of the YWCA cabinet. Her election to these leadership positions indicates her standing in the campus community. So does her induction in April 1945 into Theta Sigma Upsilon, an invitation-only service sorority. But after VE day on May 8, The Breeze offered a sharp remainder of her alien status when an editorial urged Madison students to endorse total war against Japan and declared, “We have to kill the Jap solder for he won’t surrender. Death on the battlefield is the highest death to the Japs, and it is our own boys who have to fight these tricky, fanatical soldiers.”

I can’t tell if Nemoto returned to Rohwer during the summer of 1945 or not. Severe rationing caused President Duke to cancel spring break a few months earlier due to the national shortage of fuel, and travel remained restricted. Rohwer’s registration record indicates she was officially released Jan. 2, 1944 to “Harrisonburg, Va,” and another notation says she received permission to travel to Kansas City to attend sister Kimi’s wedding, which occurred on June 1, 1945. She could have stayed in Missouri after the wedding, traveled to Rohwer, or returned to Harrisonburg. Where was she when the US bombed Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki on August 9? Where was she when ‘VJ Day’ was announced on Aug. 14, 1945, and the surrender documents signed on Sept 2? I wish I knew. It must have been a very difficult summer. By September 15, she was back on campus for her senior year.

“College in Peace,” proclaimed The Breeze. Now living in Senior Hall (Converse Hall) and still a member of the YWCA, Nemoto was assigned her own little sister, a white woman named Frances Clark Bethel, one of 473 freshmen admitted. As a senior, she qualified for a wide array of social privileges, like the ability to return later to campus from a date. While many white men, including newly discharged veterans, enrolled in day classes at Madison, it is not known if she participated in the post-war frenzy of dating. Historians like Jason Sokol have documented the tensions that resulted when white veterans returned to their home communities in the South and resumed old animosities toward Asian American, Latin American, and African American neighbors. Although her family remained incarcerated, Nemoto shifted her public advocacy role. She stepped down as president of the IRC, for example, and stopped giving talks about internment. She remained highly visible, however, as a leader of the YWCA cabinet and the Student Council, an elected group that, together with the class officers, formed the Student Government Association. The shift may have been a practical necessary to accommodate her senior year coursework, a series of seminars in institutional management, home management, and nutrition, along with additional requirements stipulated by the American Dietetics Association. According to the Madison bulletins for 1945 and 1946, Nemoto’s curriculum required her to complete a supervised practicum in one of the on-campus food facilities and then await her final placement in an off-campus facility. Graduation day finally came in May 1946, and I like to think that some of her family were able to attend.

Resistance and Resilience

After completing her final internship at Cook County Hospital in Chicago that summer of 1946, Nemoto went back home to Los Angeles. It was a changed place. Her parents returned there after their release from Rohwer in October 1945, but the shoe shop was long gone, and the couple had to rebuild their lives as best they could. By that time, Nemoto’s sisters were dispersed across the country. Hatsu’s husband died soon after the war ended; she remarried a Chinese American and moved to Kansas, where her second husband became a professor. As noted, Kimi had married in Missouri in 1945 and lived there with her husband. Florence, the youngest sister, secured a release from Rohwer in May 1945 to work in Washington DC, where she married and settled down to raise her family. Yuri Nemoto landed a position at Temple Hospital, where she met Amor Tamayo, a Filipino immigrant. They married in October 1948, then resided at 2907 Hobart Blvd in Los Angeles, not far from where Nemoto grew up. These facts cannot convey adequately what post-war life was like, however.

Many scholars have documented the long-term effects of forced incarceration on Japanese and Japanese American families. The trauma they experienced was both physical and psychological, stemming from the violence they endured, the dehumanizing conditions in the camps, and the enormous damage to their individual and collective sense of self-image. Yuri Nemoto was just one of an estimated 120,000 US citizens affected by this tragedy. Smart and confident, she learned in Little Tokyo how to survive life in a racist society that considered her a second-class citizen. Against the odds for a Nisei woman in the 1940s, she had already completed a semester at UCLA, and when offered the chance to complete her degree a continent away, she took it. At Madison, she resisted the racist stories told about Japanese people in popular culture and the media by creating a counter narrative that undoubtedly relied on her own lived experiences. Letters and phone calls from her sisters and parents provided crucial support and encouragement. She had help, as well, from some sympathetic whites, like the Disciples who arranged her scholarship, the administrators who approved her transfer, and the students who accepted her into the Madison community. She may also have benefitted from the support of Black staff who worked at the college and in Harrisonburg. There’s still so much more to learn about her experiences. A conventional reading of Nemoto’s story would interpret her success as ‘triumph over adversity,’ but a truer one would emphasize her resistance and resilience.

The racism and xenophobia that made Yuri Nemoto Madison’s first Asian American student didn’t disappear when the war ended. In an important essay in Asian American Studies Now: A Critical Reader (2010), Robert G. Lee documented the emergence of the “model minority myth” in the Cold War era, when whites consciously constructed a harmful, new, Asian American stereotype in response to African American activism during the Civil Rights movement. The model minority myth continues to have a damaging effect today, especially for Asian American college students. On this campus, like many others, Asian American students didn’t enroll in significant numbers until the 1970s, when actual desegregation began to occur, but even then they were very few.

I wonder what Nemoto would think of JMU today. I can’t ask her because she passed away in 2018. However, given her experiences here, I think she would be pleased to see multiple Asian student organizations, the APIDA Faculty Caucus, the Asian Studies minor, Japanese language classes, and study abroad programs in Japan. Yet, she would also see that only 4.4% of JMU undergraduates identify as Asian or Asian American, whereas 74% identify as white. She would know that, despite the condemnations of Japanese American internments at concentration camps like Rohwer, anti-Asian hate is rising nationally and globally. This is especially evident in Los Angeles County, where just this month, Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (May 2022), a survey by Cal State Los Angeles found that two-thirds of Asian American and Pacific Islander residents fear rising racial attacks. When I reflect on Nemoto’s story, I know she would want us to stand up against the racism and bigotry that still affects our campuses and our communities.

SOURCES CONSULTED

The Breeze, 1940-1946

The School Ma’am, 1943-1946

Madison College Bulletins

Leslie Bow, Partly Colored: Asian Americans and Racial Anomaly in the Segregated South (2010)

US federal census schedules

Los Angeles city directories

as well as other primary and secondary sources linked in the text, above