The idea for a building for alumnae emerged in 1920 as President Samuel Page Duke considered the needs of a growing campus. He became president in August 1919, as the first World War and global pandemic were still winding down and disruptions persisted. The Harrisonburg Normal School (formerly the State Normal and Industrial School for Women at Harrisonburg), which had closed temporarily during the pandemic, was bursting again with new students. The young women came from all over Virginia, eager to gain the kinds of skills and knowledge needed to join the workforce, which desperately sought women workers to replace men in all kinds of fields. Duke need funds for everything: dormitories, classrooms, offices, and even the social spaces so necessary for student life. The Alumnae Association quickly stepped in to help raise money.

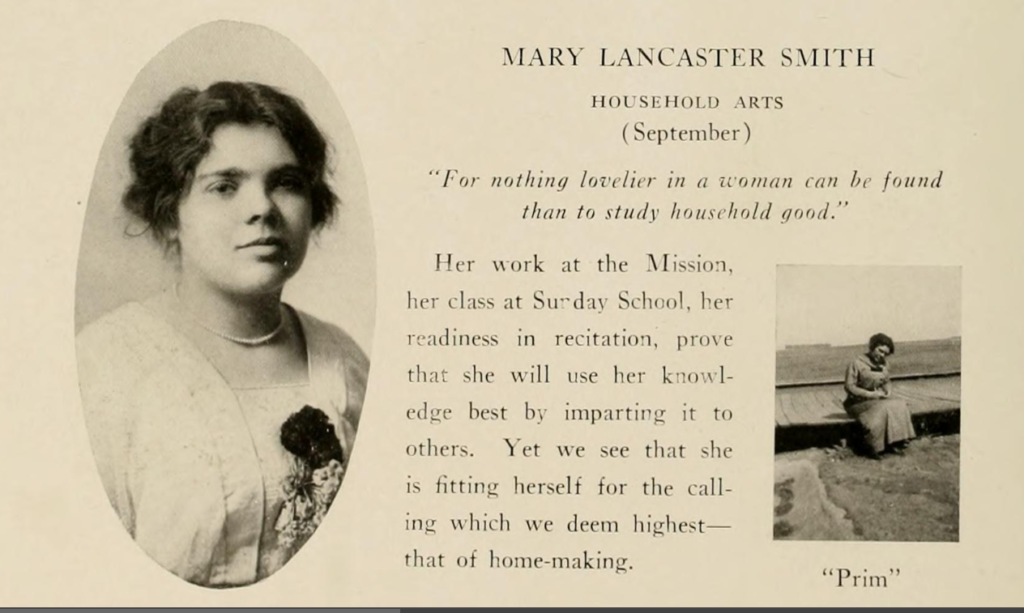

The project for Alumnae Hall formally launched on November 29, 1920, at a luncheon in Richmond, Virginia. Many of the Normal’s approximately 5,000 alumnae were in the city for the annual state teachers’ conference. As usual, the event included a large HNS reunion lunch and meeting, this time hosted by the brand new Richmond alumnae chapter. Duke presided, but the Normal’s first president, Dr. Julian Ashby Burruss, then serving as president of Virginia Polytechnic, also attended and served as toastmaster. At the end of the toasts, Mary Lancaster Smith (’14) stood and made a motion to finance a novel structure for use by both alumnae and current students. The roughly 125 alumnae present eagerly voted and carried the motion. [“News and Views”, Dec. 1920, VA Teacher, p293.]

Sources reveal the unusual funding plan: the alumnae would help raise the money. How exactly it came about is still unknown, but Mary Lancaster Smith, the woman who had the honor of offering the motion, likely played a crucial role in developing the project. She certainly knew how much graduates loved Bluestone Hill, a name that reflected the deep attachment they had to the physical place as well as to each other. In fact, alumnae often came back to town to attend graduation ceremonies and the concurrent meeting of the Alumnae Association (established in 1911). The association already sponsored a modest Student Aid Fund that helped seniors in need complete their studies. Smith, a domestic science and dietetics teacher in Richmond, was an active alumna and understood how the scholarship fund might serve as a model; she served on the advisory board of the Virginia Teacher, a new publication produced at the Harrisonburg school, and she was inaugural president of the Richmond alumnae chapter, formed in March 1920. As news spread from the capital across the state, HNS alumnae responded with enthusiasm and put their networks to good use.

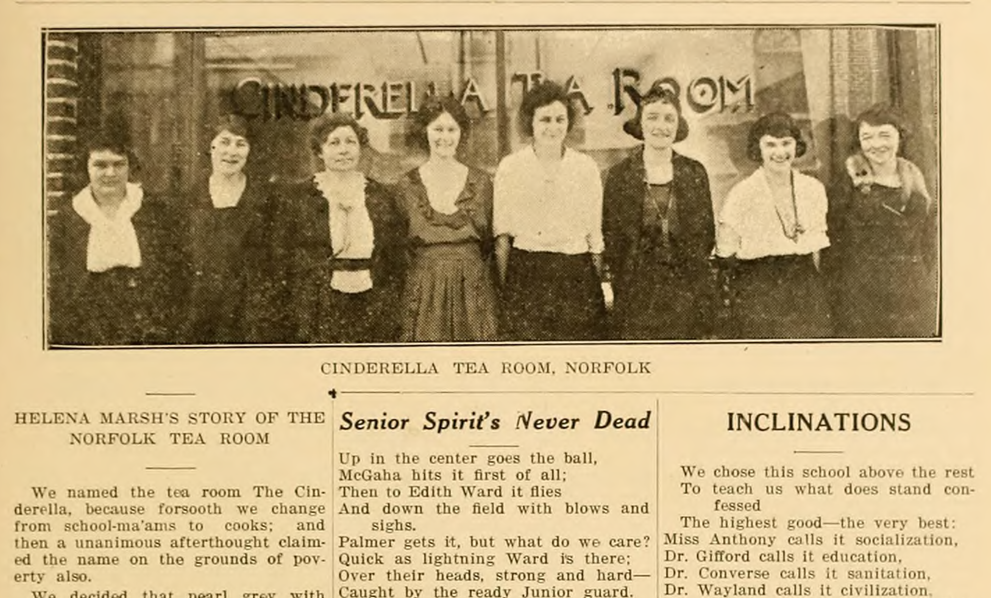

“News and Notes of the Alumnae” in the Virginia Teacher reported on the fundraising methods the women used and tracked their progress. The 1921 issue showed personal checks coming in from all over, including from alumnae who lived out of state. Some chapters raised money from the public at large. The Hampton Chapter opened an “up to date eating place” called The Brown Teapot to raise money. The Norfolk chapter also had a tea room–named for Cinderella. More research is needed to determine how unusual their organized philanthropy was. Wealthy women from colleges like Vassar had a long tradition of donating money, but the Normal’s alumnae were generally from modest families and drew low salaries. They knew they had to combine their donations to reach their goals.

An editorial in the Virginia Teacher called their philanthropy “An Expression of Love and Loyalty” and explained why they gave so enthusiastically. Of course, it said, their donations were a “small return for what the institution has meant to their lives, its lessons of cooperation and high-spirited endeavor, . . . its insistence upon the values of steady, honest, character-building achievement, and its delightful memories of associations.” The author admitted that the building would serve as a “monument” to the alumnae and to their essential role in “the upbuilding of a great institution,” but more than that, the women knew that in supporting HNS they were contributing to “the upbuilding and development” of the state schools and thus, to the commonwealth. The editorial is worth reading in its entirety for it underscores how these women connected the private benefits of public education to the public good.

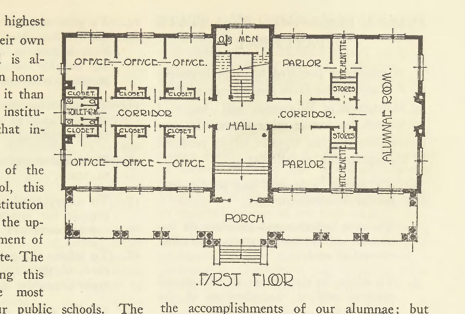

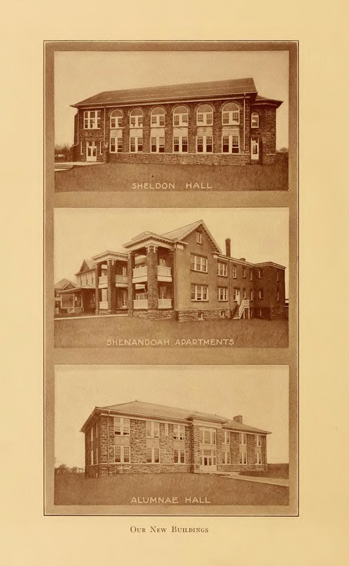

By April 1921, the women had raised enough money to secure the Virginia Normal School’s Board’s authorization to break ground and proceed with construction. Surviving blueprints and renderings indicate how unique the structure was. To reduce costs, the campus architect, Charles Robinson, adapted existing plans from Dorm #1 (called Jackson Hall in 1921, currently Darcus Johnson Hall) so the exterior would remain identical to its twin building opposite the Quad. Inside, however, it had a large reception room and two parlors with adjoining kitchenettes on east end of first floor (currently vice presidents’ suites). Six offices occupied the west end; these were dedicated spaces for student organizations and for the Alumnae Association, itself. Upstairs, there were six guest bedrooms, all en suite, so visiting alumnae could stay right on campus, and two large meeting rooms for the Normal’s two literary societies, which served as the students most prestigious social organizations (currently the President’s Office suite). By blending space in this innovative way, the alumnae were assured of close contact with the young women who would eventually join their ranks. The building thus facilitated the kind of mentoring and networking relationships that have long characterized the institution. [VT April 1921, vol 3, issue 2]

The building was mostly completed by early summer 1922, but funds were running out. Several other costly structures were also under construction. There was also another problem: grading of the north side of the Quad was needed to level the sloping site, which had a higher elevation than the south side, and excavations apparently led to the discovery that a massive rock formation right in front of the new alumnae building was far too big to move. Today, the rock is a beloved landscape feature, but in 1922, it was an eyesore disrupting plans for a set of grassy terraces. To raise more funds, Duke approved housing 32 young women in the upstairs alumnae guest rooms for the 1922 summer session. That fall, the structure formally opened. The brand new student newspaper, called The Breeze, had its first office in the southwest corner office of the alumnae building (now the Provost’s office). [“News of the Alumnae” VT vol 3, issue 8]

Over the main entrance visitors can plainly see the words ALUMNAE HALL in the stone. This is the only structure on campus with its name carved permanently into the facade as a memorial to the women who built it. Altogether, the alumnae raised $12,550. The rest came from the state coffers ($20K) and the college’s own operating budget ($11K). A modern inflation calculator puts the alumnae’s share at $221,325 in 2022 dollars. That’s not very much by modern standards, of course. Today, university buildings cost millions of dollars, but the financing model is much the same as it was in the 1920s–a blend of public resources and private philanthropy. As the alumnae of JMU continue to give to their beloved alma mater, they may draw inspiration from the women who shaped the institution so many years ago.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES

See Dingledine 131-33

Chappelear, “Buildings and Grounds” VT 12, issue 4 (1931)

The Virginia Teacher