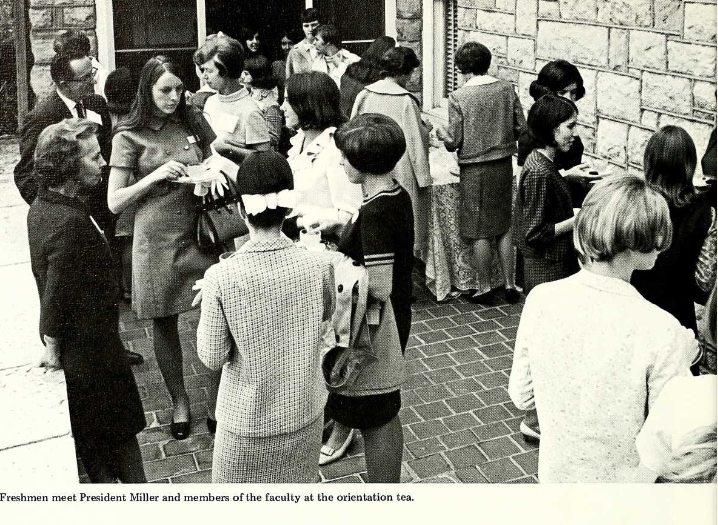

I recently gave a short talk to JMU alumni at a Women for Madison tea party. The topic was the history of tea parties on this campus, which were commonplace from the 1910s through the 1960s. The event was part of JMU’s annual Bluestone Reunion, which marks the 50th anniversary of each graduating class. This year’s honorees were members of the class of 1974, and several alums vividly remembered the welcome tea reception they attended at the President’s house, Hillcrest, in the fall of 1969. It turns out that that was the last welcome tea held at Madison College.

Tea parties have a long history at this institution–they are well documented through photos in yearbooks, napkins and favors pressed into alumni scrapbooks, and actual artifacts in the form of silver tea pots, serving trays, and china. These survivals, carefully recorded and preserved, tell us that tea parties served an important function and were an defining part of campus culture here.

How and why did tea become important here? Well, the origins of the modern tea party lie in collective memories of colonial America. Tea was once an expensive, imported commodity, you’ll recall. Only the wealthy drank it. In colonial Virginia, both the production and consumption of tea required elaborate rituals–heating the water, spooning the loose leaves into an elegant pot, swirling them around, pouring through a delicate strainer, and then sipping carefully from a handle-less cup. Fashionable people, always members of the slave-owning planter class, used tea for social purposes, of course, but they also understood tea’s symbolic role as a sign of wealth, status, and power. By 1776, tea also had close associations with Southern hospitality, gentility, and refinement, all of which were on display when the lady of the house hosted.

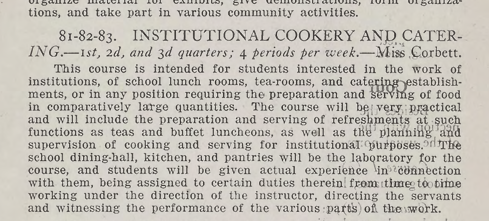

By the time this institution’s doors first opened in September 1909, the Colonial Revival was in full swing, and that movement brought a resurgent interest in tea parties. Students at what was then called the State Normal and Industrial School for Women at Harrisonburg came from modest households, not affluent ones, and expected to learn feminine social graces alongside vocational skills. Cooking and nutrition classes, for example, were part of the Domestic Science curriculum that prepared women to manage commercial and institutional kitchens, work as state agricultural agents, or serve as professional dieticians. But it’s clear that women also learned how to prepare and properly serve dainty tea fare, as well as conventional foods. The 1916 Bulletin, for example, promoted a new course in Institutional Cookery and Catering that intended to train students for work in “tea rooms,” among other sorts of facilities.

Tea mattered because it was the perfect repast to accompany the many kinds of women’s activities that took place in the afternoon. Tea wasn’t lunch or dinner–it was a time to socialize with just a few friends in the home, certainly, but in the early 20th century, tea was also an occasion to host a garden club, a hospital board, or a suffrage meeting. Whether large or small, a tea required careful planning and execution. Attendees expected fine tablecloths, the hostess’ best china cups, and fancy finger foods, all artfully arrayed. The hostess sat next to a special “tea table” (so-called because of its height) to pour each cup, while guests passed handled trays like the three-tiered ‘curate.’ A large tea was still a formal affair, but the food was set out buffet-style on a dining table, and two or three women took stations at the end to pour. Photos from Madison College document both kinds of teas.

No matter if there were three women or fifty at the tea, the food was similar. There had to be sweets and savories: slender, 2-3 inch ‘finger’ sandwiches on thin bread filled with finely chopped chicken salad or maybe cream cheese and watercress; canapes with a smear of olive paste; tiny lemon or jam tarts; and fine, wafer cookies. All of it had to be delicate and small enough to be eaten without a fork. Period cookbooks gave specific menus, in fact, along with suggestions for displaying the dainties to best advantage. The ladies tea should not be confused with the British high tea–that was a different thing entirely, more of a meal, in fact. The American tea was just enough refreshment to keep the guests happy.

Today, the phrase tea party brings to mind a kind of frivolous, fussy behavior–when do I add sugar? can I have lemon? How do I hold this tiny handle?–but American women actually used tea parties for serious purposes. Before the 1920s and even into the 1930s, women were typically excluded from public restaurants unless accompanied by a man. A tea could be hosted in a home, a church basement, or on a campus, wherever and whenever women had a need to gather. Black women held teas, too, and like white women, did so for all sorts of reasons–to conduct business, to hear speakers, and, especially, to raise money. As this post explains, in 1921 this institution’s very own Alumnae Association raised money to build Alumnae Hall by establishing temporary tea rooms in Richmond and Norfolk. On campus, students held teas to raise money for their clubs and organizations in the days before mandatory fees.

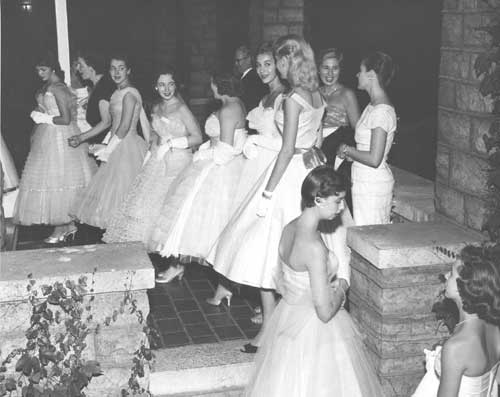

After World War II, however, the function of an afternoon tea party changed. Even though veterans were back at work, there were more and more women employed outside the home and more of them had degrees, like the women of Madison College. By the early 1950s, anxiety over changing gender roles resulted in a new kind of ultra-femininity, the kind epitomized by Dior’s New Look, with its tiny waist, full bosom, and long, crinolined skirt. College campuses hosted tea parties for dances and receptions, not only business meetings and social clubs. At Madison, the Social Committee organized these events, polished the silver, arranged the flowers, and decorated the rooms. A similar group called the Standards Committee promoted the proper decorum, dress, and deportment still expected of a Madison student as a Southern, white woman.

The most important tea at Madison College at mid-century was without doubt the new students’ reception. Held at Hillcrest House and hosted officially by President and Mrs. Miller, it featured a long receiving line where the young women got their first chance to meet the senior administration and members of the faculty and demonstrate their good manners. Other teas were also held, of course. The Seniors held teas in a special reception room in Senior Hall, and designated tea and reception rooms were also used in Alumnae Hall, Varner House, Moody Hall, and in the off-campus sorority houses. In surviving photos, faculty women, faculty wives, and dormitory hostesses or house mothers are always present, often pouring the tea. In this way, campus teas still provided a way for young Madison women to observe and emulate the older ones.

But social changes started in the 1960s could not be stopped. In 1966, Madison received approval to become fully co-educational and to desegregate. The presence of men in the residence halls dramatically altered campus culture, especially the kinds of social events hosted here. Although still a fairly conservative place, culturally, more women students at Madison embraced feminism as the 1970s arrived. This was the decade of NOW, ERA, and the sexual revolution, after all. Even the Faculty Women’s Caucus organized in support of equal pay and an on campus day care.

By the 1970s, then, the ladies tea party was no longer an everyday part of life on this campus, mirroring its decline in American society. Women graduates needed a different skill set as they moved up corporate ladders and into boardrooms. Closely associated with a certain kind of refined femininity, the tea party shifted to special occasions when only women gather, like baby and bridal showers. The popularity of formal, British High Teas, however, perhaps a reflection of Downton Abbey and similar shows, reminds us that teas retain their allure for many people. In a fast-paced, fast-food world, they provide an opportunity to slow down and savor good company.