Maybe it’s all the cultural geography I’ve read, but I find the idea of mapping my place in the landscape of open learning very intriguing. Am I digital visitor or a resident? In my forthcoming book, I explore (among other things) the way cognitive mapping works to help people navigate their place in the cultural landscape of a community; I’m especially interested in the way that our attachments to physical places serve as mnemonics for experiences or events (both positive and negative) crucial to identity formation, especially civic and racial identities. Among other things, I consider the way parades function—a group of people processing deliberately by iconic buildings and monuments serves to inscribe shared values on the landscape but also works to unite the marchers and the watchers as members of an imagined community. (People can also be excluded from participating and have traumatic memories of events and places.) I wonder if a similar kind of attachment and identity can be formed in online spaces. Seems plausible, right? If I consider the web a place and participate in certain online communities, then I’m having experiences and making relationships that shape my identity as a member of those communities. The piece I’m puzzling out concerns the mnemonic structures. What takes the role of the physical marker, the iconic building or monument or sign? Is it the architecture of a web domain? The WordPress page, the Twitter profile, the Facebook page?

To explore these ideas further, I decided to delve into visitor and resident mapping exercises. Through the Open Learning17 cMOOC, I had already read Laura Gogia’s post on V&R mapping, and she led me to read Donna Lanclos’s keynote on Teaching, Learning, and Vulnerability, which included more on mapping exercises, as well as a Periscope of Bonnie Stewart’s recent presentation at Keene State (slidedeck here) and David White’s various posts and videos at JISC. (These folks all know each other and work together in various ways and so if you follow my trail, you’ll quickly see the interconnectedness of these sources.)

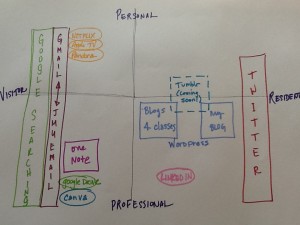

A mapping exercise is a great way to visualize one’s own practices online and reflect on them. Here’s what mine looks like. It wasn’t difficult to do—the hard part was finding the colored markers (fortunately I have a daughter who’s a tween). It corroborates my approach, which has been to keep most of my personal stuff, well, personal. Note I have almost nothing in the upper-left corner. I don’t do Facebook or Instagram, but I am considering Tumblr as a way to share certain photos and curate digital images and such. I could do more with Twitter: the map shows my personal activity: I also manage two other Twitter accounts, one for an organization and one for a group on campus, but those don’t count because I’m not ‘me’ when I’m tweeting under those handles. Could I do more with LinkedIN? Should I? I am hopeful that my blog will become more ‘residential’ in the future.

Why Twitter? I joined in 2012 and I consciously chose it because I wanted (ok, needed) to connect to other scholars who were working on public history, collective memory, race, and place. It also connected me to a group of administrators in public higher ed who share my concerns about defunding, attacks on liberal education, adjunctification, student debt, inclusivity, and myriad other challenges. Sometimes, the two communities even intersect, as they have in recent conversations about memorials to slaveholders and white supremacy on campuses. And that topic brings me back to physical markers that serve as mnemonics for individual and group identity formation.

Obviously, there are no physical markers on the Web. But there are visual markers that tell us, whether we are visitors or residents, where we are. There are signposts and trails everywhere. And the current fascination with personal branding, even in the hallowed halls of Academe, reflects the recognition that our digital identities are tied to, derive from, and are shaped by the markers evident in the myriad digital spaces we enter. Having a consistent brand (same color or font, photo, logo) is imperative, it seems, as we travel around the internet. My undergraduate students understand the way visual markers work to create digital identities, but at this stage of their lives they seem more interested in promoting multiple selves than in crafting a coherent persona.

My identity on Twitter, the place I reside most, is still evolving. I chose a photo that depicts me talking and gesturing with my hand because I happen to be a talker and gesturer. My profile includes words that chiefly convey my professional identity yet there is a nod to my private self in the references to my coffee addiction. Coffee isn’t unique to me, but it is actually a significant part of who I am and how I spend my time. The photo of the coffee cup I took on a visit to Charleton’s Coffee House in Colonial Williamsburg, so it also serves as a mnemonic for me of that trip and a physical place (Williamsburg) that is crucial to my professional identity since I went to W&M and worked at CW.

When I go to my Twitter site, I see signs of who I am IRL and I assume others see them, too. But I’m not aggressive in promoting my self this way and perhaps other residents will see me as merely a visitor as a result. In her Keene State talk, Bonnie Stewart noted that open citizenship occurs in “quantified” spaces. The number of followers you have, the number of comments posted, these quantities influence how others see you and whether they will interact with you or not. So those numbers serve as visual markers of your identity, except they are created by others.

Something happens when you move out from your own Twitter timeline and enter a communal space like the one defined by #openlearning17. There, I see familiar “faces,” meaning the digital identities of other members of this online community, and I remember who is who by virtue of their profiles and handles. The people in that digital space are different each time, but the place is always the same—the white Twitter boxes, the blue Twitter bar, the navigation buttons, the bird. I see the same thing when I check in over at #twitterstorians or #AACU17 or even #JMU. It’s a corporate space, designed FOR users, not BY users. I can’t get lost in the Twitterverse, not really. The markers always tell me where I am and who.