I’m republishing this Feb. 2019 post today 6/20/20 with a disclaimer: it contains references to historic ideas, words, and images that today are considered racist. I temporarily removed it because links to it were circulating on mass media and social media, and portions of it were taken out of context.

Blackface minstrelsy has a long history on this campus, so in light of recent revelations about state officials’ participation in related activities I thought I’d pull together some information for students wondering what the heck is going on. First, as Dr. Rhae Lynn Barnes noted in her recent WaPo essay, “The Troubling History Behind Ralph Northam’s Blackface Klan Photo,” minstrelsy was absolutely “central to civic and campus life in 20th century America.” White men, young and old, poor and elite, uneducated and erudite, not only used “the profits of amateur blackface to build white-only institutions” but, more importantly, to affirm their political, economic, and cultural power. Barnes’ forthcoming book, “Darkology,” will shed important new light on this topic, expanding earlier studies by scholars like Eric Lott. Second, what I’d like to add, and what blackface on this campus shows, is that white women actively supported their efforts.

I’ve written about the way minstrelsy historically served as a key component of this campus’s culture in two previous blog posts, Confederate Heritage at JMU, and Alumni Scrapbooks and Collective Memory. From 1908 until roughly 1958, the administration and faculty actively encouraged blackface as evidenced by its presence at official school events, in its student organizations, and its publications. The evidence is overwhelming that the all-white, female student body participated enthusiastically in these caricatures; among other things, they routinely staged their own amateur minstrel shows, photographed themselves in blackface, and proudly saved programs that stated their real names and the roles they played. They also referenced blackface in other ways: in cartoon sketches of black people that decorated ephemera, in racist dialect that appeared in song lyrics and plays and poems, and in initiation rites for clubs. Just as it was in American culture, broadly, blackface on this campus functioned as a form of cultural violence against Black people. Along with other behaviors, it supported the cultural construction of white, Southern womanhood even if “not all students” participated. That these young women were training to become teachers must also be recognized, for many familiar children’s songs, like Oh Susanna and Cindy, Cindy were minstrel songs.

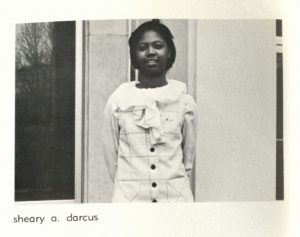

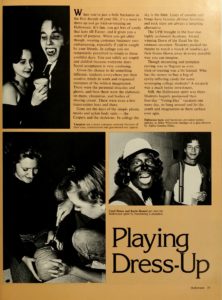

Although it did start to diminish after WWII, blackface activities persisted here, as they did on other all-white Virginia campuses, through the era of the state’s massive resistance to federal desegregation mandates in the 1950s-1960s and into the decades of resistance to affirmative action in the 1970s-1990s. It is not surprising, then, to see in yearbooks and student newspapers evidence that some individuals who attended JMU in the 1980s “blacked up” at private parties, in homecoming parades, or at Greek events. Like earlier forms of blackface in the the Jim Crow era, these performances cannot be separated from the broader context of organized white resistance to higher education integration. Madison College admitted its first black student, Sheary Darcus (now Johnson), in 1966, and its first black graduate student in 1969, however, desegregation proceeded very slowly throughout the 1970s. In fact, Virginia’s official policy of resistance did not end until the administration of Gov. John Dalton began in 1978, the same year that the Supreme Court’s famous Bakke decision gave rise to the concept of “reverse discrimination.” What was it like to be a Black student or staff member or instructor at Madison at that time? In previous public history seminars, my students and I explored the transformation of this institution in a series of web-based exhibits called Madison in the 1970s. That project demonstrates that the changing trajectory of American higher education, including contemporary efforts to make JMU more diverse and inclusive, are very recent indeed.

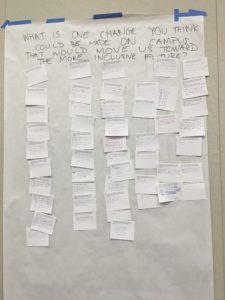

Viewing blackface as cultural violence, as an intentionally demeaning, dehumanizing activity with a long history, helps correct the perception among many white Americans in 2019 that it’s just harmless “play”. Last fall, I made a short presentation at an event called “JMU’s Legacy of Exclusion: Confronting our Past and Creating a Culture of Inclusion.” Offered under the auspices of the History and Context Committee of the university’s Task Force for Inclusion, my talk preceded a facilitated dialogue with about 80 JMU students, including students affiliated with the Center for Multicultural Student Affairs, Student Government Association, Student Ambassadors, and Honors. The event occurred only days after a digital photo of a former adjunct instructor in blackface (he was at a Halloween party) went viral on social media. And it was clear that while many students were aware of the incident and found it offensive, some were perplexed by all the fuss, and some were deeply, viscerally upset. In small group discussions led by trained facilitators from Dr. Lori Britt’s communications class, they shared their reactions to my research into JMU’s segregationist, white supremacist history, and they explored the institution’s contemporary values. Finally, they considered the strides JMU has made in recent decades and what remains to be done in the future.

A clear theme emerged: many felt that “educating students” about the past was necessary “to make salient the exclusive [sic], inherited structures and practice” that “keep us from being as diverse and inclusive as we want to be.” (Report, 8 and Appendix) Blackface is one of those “inherited practices” designed to affirm white superiority and black inferiority.

A clear theme emerged: many felt that “educating students” about the past was necessary “to make salient the exclusive [sic], inherited structures and practice” that “keep us from being as diverse and inclusive as we want to be.” (Report, 8 and Appendix) Blackface is one of those “inherited practices” designed to affirm white superiority and black inferiority.

Last Thursday, my current class discussed the revelations about their elected representatives in Richmond and took time to peruse old yearbooks online. We were scheduled to study oral history as a branch of public history, but the news that morning of a third legislator who had “blacked up” in college presented a teachable moment. The digitization of archival materials like yearbooks had been the topic of a previous class, and I’m proud to say they rose to the occasion. When I asked them what one should do with knowledge of the history of blackface on campus, they said: take responsibility for it, show remorse, seek remedies.

Responsibility. Remorse. Remedy.

We’re on the right track.

Thanks to the SCOM 447 students who facilitated the dialogue and prepared an “External Report for JMU’s Legacy of Exclusion: Confronting our Past and Creating as Culture of Inclusion.” especially Celia, Jacob, Daniel, John David, and Georgina.