I’m republishing this August 2019 post today 6/20/20 with a disclaimer: it contains references to historic ideas, words, and images that today are considered racist. I temporarily removed it because petitions linking to it were circulating on mass media and social media, and portions of it were taken out of context.

If you understand that a college campus is a commemorative landscape, that its named buildings, statuary, roadways, plazas, and so forth all comprise a text that can be read for insights into the institution’s cultural values, then you’ll appreciate it when I say that JMU’s Quad is a kind of lesson plan. Conceived by Dr. John Wayland, first professor of history at the State Normal and Industrial School for Women at Harrisonburg and head of the department of Social Studies until 1931, the plan relies on the associative properties of monuments, which call forth the great deeds and virtues of the person or persons memorialized. Wayland understood these properties very well–it’s why he took students on so many “excursions” or visits to local monuments and historic sites, as I described in a previous post about Confederate heritage on this campus. At JMU as elsewhere, people are asking new questions about individual buildings that memorialize historic figures: who are the persons honored, what did they do to be commemorated, and what message does the naming convey? In this post, I’ll answer these questions and also show how the Quad’s named buildings collectively taught future teachers a period-specific interpretation of the history of the Shenandoah Valley, of the Valley’s place in Virginia history, and the alma mater’s place in both.

Laying the cornerstone for Science Hall, April 1909. Construction began the previous fall and the building opened in September 1909. JMU Special Collections

The first buildings constructed on the Quad had functional names: Science Hall and Dormitory No. 1. Science Hall primarily referred to the new science of education taught at the Normal. Through courses in specialized subjects and in pedagogy, but especially through the innovation of supervised field placements in actual classrooms, Normal students were exposed to the professional standard or “norm” they had to meet to earn teaching certificates. The first and only academic building in the 1900s, Science Hall also housed science-based courses in nutrition, household arts, and agriculture–the industrial part of the curriculum. The name of the other building, Dormitory No. 1, referenced the residential nature of the campus, which was designed from the start to be a place where faculty and students formed a living-learning community organized around shared values. Instilling these values proved difficult because over-enrollment meant that many students actually boarded in private homes in town, but distinctive rituals like chapel exercises, communal meals, and uniform clothing helped. The next three buildings constructed, Dormitory No. 2, the Student Services Building, and Dormitory No. 3 also received practical labels. As the campus grew in size and, importantly, stature, the administration decided that a coherent, didactic naming plan was needed.

Wayland recorded the decision and his leadership role in his diary:

1917, June 3-5. “Steps were taken to name the buildings. President Burruss appointed Miss Mary Bell and me a special committee to take votes and report. I had suggested the matter some months ago. From a list of 14 names selections were made by 1) the student body 2) the alumnae who were at commencement and 3) the faculty.”

Bell served as Burruss’s personal secretary, the registrar, and librarian, so she likely helped type the list and tally the votes. Burruss proclaimed the new names at the graduation ceremony on June 5: Science Hall became Maury Science Hall for Matthew Fontaine Maury; Dormitory No. 1 became Jackson Hall for Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson; Dormitory No. 2 became Ashby Hall for Gen. Turner Ashby; the Student Services Building became Harrison Hall for Prof. Gessner Harrison; Dormitory No. 3 became Spotswood Hall, for Gov. Alexander Spotswood; and the former farmhouse occupied by faculty women became Cleveland Cottage for Miss Annie V. Cleveland. The list of fourteen names hasn’t been found, but when Burruss shared the results of the voting with the Board of Trustees, he said it contained “the names of a large number of men of historical and educational prominence, who were connected in some way with this section of Virginia.” (Burruss, 1917) A closer look at these six notable people explains why Wayland, Bell, Burruss and the others felt they deserved commemoration at a teacher training school for white Southern women.

Burruss’s report refers to Maury as “a scientist, author, and educator who taught and studied in the Valley of Virginia.” Born in Fredericksburg, Matthew Fontaine Maury earned fame as a US Naval scientist, specifically as one of the world’s early oceanographers. In 1861, he resigned his commission to join the Confederacy as a commander. During the Civil War, he developed a marine mine, but due to an old injury, he mostly served as a CSA envoy in England. During Reconstruction, he tried unsuccessfully to create a slaveholding republic for former Confederates in Mexico, and eventually settled in Lexington, a town at the southern end of the Shenandoah Valley, where he had been offered a courtesy position at Virginia Military Institute. A vocal advocate for public higher education, he helped establish Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College (now VA Tech) in 1872, and received several offers to lead colleges in other states; he turned them down, purportedly so he could stay close to Robert E. Lee, then president of nearby Washington College (now Washington and Lee). As viewed in 1917, then, Maury had directly contributed to the expansion of science and of higher education in the Valley and in Virginia, broadly, but his loyal service to the Confederacy and its Lost Cause also commended him. In fact, the Lost Cause was so prominent at the Normal that year that references to it graced multiple pages of the School Ma’am–and four of the six persons honored with named buildings in 1917 had Confederate ties.

Christening of Dormitory No. 1 as Burruss Hall, June 10, 1913. Dr. Wayland is visible, standing on the steps, making a speech. JMU Special Collections.

Like Maury, Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson had several reasons to be on Wayland’s list. First, he, too, was a Valley resident and an academic, having lived in Lexington, where he taught at VMI before the Civil War. Second, Jackson led the successful Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862 that forced Union troops to retreat north from Harrisonburg vicinity to Winchester. This victory became a signal event in state and local history well after the war, as it was central to the mythology surrounding Jackson, a Lost Cause icon second only to Robert E. Lee. Although some secondary sources state that Jackson Hall was renamed in 1918, the vote actually occurred along with the others, for Wayland recorded in the June 3-5, 1917, entry cited above that, “Dormitory No. 1, named Burruss Hall by the class of 1913, is to be renamed next June. (It was named Jackson Hall for Stonewall Jackson).” The formal renaming of the building was postponed so that members of the class of 1913 could attend when they returned for their fifth reunion. These women had chosen the name Burruss Hall at their 1913 commencement to honor the founding president, who initially resided on the building’s second floor with his wife. Photos of the 1913 christening ceremony show a sizable crowd and Wayland offering remarks, so it was clearly a momentous occasion (one alumna, Pearl Haldeman, saved a glass shard from the bottle in her scrapbook!) and the name stuck for five years. Why Burruss suddenly felt uncomfortable about the naming is unclear; Burruss apparently insisted that no building honor a living person, however, Wayland simply said “the President made a special request” of the 1913 alumnae to change it. Since Wayland was an honorary member of the class of 1913, and since Wayland’s father served under Jackson, he undoubtedly served as the go-between and persuaded them to embrace the new name (Reunion book, Cooper).

Scrapbook page showing photos of an “excursion” to the Turner Ashby monument. The students in the lower left encircle it with their arms. The top photo shows a larger group clustered around it.

Born and raised in Fauquier County, the son of a distinguished and affluent family, Turner Ashby was an expert horseman who fashioned himself after the cavaliers of old England. In 1859, he organized a pro-slavery paramilitary group, the Mountain Rangers, and when Virginia seceded in 1861, it became the 7th Virginia Calvary. Called the “Black Knight of the Confederacy” for his striking figure and daring exploits, Ashby eventually served under Stonewall Jackson. Already a popular folk hero, Ashby’s death in a skirmish outside Harrisonburg in the 1862 Valley campaign transformed him into a martyr; in fact, the place where he fell became a pilgrimage site soon after the war, and objects associated with him became important relics as this video attests. By 1917, Wayland had published several essays about Ashby and he regularly took Normal students to visit the 1898 Ashby monument, which still stands in its iron-fenced enclosure near campus. But apparently another monument was needed on the Quad, where Ashby’s deeds could connect to a broader narrative.

In between Jackson and Ashby sat Harrison Hall, which recognizes Gessner Harrison (1807-1862). Burruss’s report called him an “educator and author, chairman of the faculty at the University of Virginia, who was born in Harrisonburg.” A studious child, he enrolled in the very first class to attend the University of Virginia, and personally knew both Jefferson and Madison. He became a professor of classics there at the tender age of 21, and, while living on Grounds with his family, he enslaved as many as nine persons. Eventually, he earned national prominence in the antebellum era as a scholar of Latin and Greek, and as faculty chairman (the chief administrative officer), Harrison continued to advance the university’s growth. Wayland, who earned his doctorate at UVa in 1907, later wrote, “All of the buildings at the State Teachers College in Harrisonburg are in a sense monuments to illustrious men and women whose names are therein enshrined. In one of them, Harrison Hall, is a bronze tablet to the man . . . whose diligent and accurate scholarship should ever be an inspiration to students.” (Wayland, 1930)

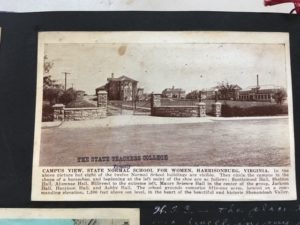

Scrapbook page with captioned postcard identifying the name of each building on the Quad and the persons honored.

Briefly known as Dormitory No. 3, Spotswood Hall was completed in 1917, the first structure built on the north side of the Quad. The name honors Alexander Spotswood, “soldier, statesman, explorer, governor of [colonial] Virginia who the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe, across the Blue Ridge into the then unknown west.” (Burruss, 1917) Spotswood’s fabled 1716 expedition crested the Blue Ridge Mountains at what is now called Swift Run Gap (where present day Rte 33, Spotswood Trail, crosses Skyline Drive) and came down into the Shenandoah Valley as far as the modern town of Elkton before returning to Williamsburg. Due to the information the group brought back, early historians of Virginia credited the group with opening the valley to settlement by English and German colonists like the ancestors of Harrison and of Wayland, himself.

Cleveland Cottage was located next to Maury Hall, just to the south. The building was originally the home of A. Moffett Newman, whose heir sold 42 acres of his farm to the Board of Trustees for the Normal’s site in 1908. After the school opened, several women faculty lived there, including Elizabeth Cleveland and her older sister, Annie. Period sources indicate that Annie Vergilia Cleveland, who taught French, became incapacitated by a lifelong illness in 1915 and remained confined to the cottage until her death in December 1916, age 68. The School Ma’am for that year contained a two-page memorial written by Wayland that described her as a loyal daughter of the Confederacy: “She loved to talk of the days when a brave people battled for a great cause; and for a good while before the end came to her she kept saying that she wanted a flag–a flag of the Stars and bars–for her very own . . . and so it was done.” As one of the first faculty, she contributed directly to the establishment of the Normal, and her name epitomized virtues associated with Southern white femininity.

The names applied to the remaining buildings on the Quad continue the pattern Wayland established. Sheldon Hall, for example, started in 1923 and built in two phases, honored Edward A. Sheldon, an Oswego, New York, professor who pioneered the normal school method for teacher training. Alumnae Hall honors the early women graduates who established the Normal’s reputation and who donated funds for its construction in 1922. Walter Reed Hall, completed in 1926, memorialized Dr. Walter Reed (1851-1902), who was credited with discovering the cause of yellow fever. His contributions were appropriate since the building housed health education programs when it opened, but equally important, he spent much of his adolescence in Harrisonburg, his stepmother’s hometown. (This building was renamed for state senator George Keezle, who helped establish the Normal, after Keezle’s death.) And then there’s Wilson Hall, named in 1931 for President Woodrow Wilson.

This structure, the largest building by far, dominates the Quad physically and symbolically, just as the Rotunda at UVA looms over Jefferson’s Academical Village. Instead of a domed library signifying the universe of knowledge, it had always been designated “the main administration building.” Housing the president’s office and sited at the top of an actual hill (Bluestone Hill), the building represented white male authority and hierarchy and so the name it carried had to have similar weight. It’s interesting to speculate why ‘Madison’ wasn’t chosen–President Duke was already thinking about a future Madison College. But Wilson more readily fit the pattern, for he was born in nearby Staunton, earned a PhD from Johns Hopkins, and became president of Princeton University before winning election as governor of New Jersey and President of the United States. Author, educator, statesman, Virginian, defender of segregation–Wilson’s name sent a powerful message.

“I have no patience with ‘history for it’s own sake’ any more than I have with art for its own sake,” Wayland declared. In his popular 1914 text book, How to Teach History, and in a remarkable talk he gave to the Normal faculty in 1916, Wayland argued for teachers’ use of “mnemonic devices” and lauded the “value [for learning] of things that can be seen, such as buildings, monuments, relics, models, maps, pictures, [and] diagrams.” His methods worked well. Normal students clearly knew and cherished the memories of the individuals honored on the Quad. Postcards pasted into scrapbooks, bronze plaques inside hallways and auditoriums, images and poems in yearbooks, excursions to historical sites, and lectures in classes all worked together to reinforce the lessons associated with the campus’s commemorative landscape. Collectively, the Quad’s named buildings celebrated the Valley’s role in the development of colonial and Early National Virginia (Spotswood, Harrison), its importance to the Confederacy during the Civil War (Ashby, Jackson), its continued contributions during the Progressive Era (Maury, Reed, Wilson), and most of all, the value of the Normal school (Alumnae, Sheldon, Cleveland). Together, they advanced a very particular interpretation of the past, one that white Virginians considered appropriate and necessary in the early 20th century.

Sources:

School Ma’am, 1917

Class of 1913 Reunion Book

Kathleen Harliss scrapbook

Pearl Haldeman Stickley scrapbook

Wayland, Virginia Valley Records

William Cooper, History of the Shenandoah Valley, v. 3

Wayland Papers, SC 0258

Burruss report, June 30, 1917