Everyone wants to draw lessons from the past right now. My Twitter TL is full of links to news articles comparing the COVID-19 crisis and the 1918 influenza pandemic. There’s even a #COVID19syllabus project that gathers recent articles and supplements them with scholarly books and articles. So I couldn’t ignore the fact that my campus closed in 1918, just as it closed in March 2020. Sitting in Webex meetings with other administrators, I wondered what happened back then, what decisions those administrators made, and what impact influenza had had on the State Normal School at Harrisonburg. [read more]

Background

As the United States entered World War I, men from all walks of life gathered at U.S. military camps to train for combat. That context matters to our story because scholars point to Camp Funston in Kansas as the likely place of initial outbreak in this country. How the flu came to Funston in the spring of 1918 remains unclear; whenever and wherever troops moved, they took the so-called ‘Spanish influenza’ with them. The term is, of course, a misnomer: neutral Spain offered regular, candid reports of the epidemic occurring within its borders, whereas combatant nations intentionally hid that information. To citizens reading the international news, it appeared that Spain was the source of the pandemic. By late August, the ‘Spanish flu’ or ‘grip’ had reached Virginia. The first documented case in this state appeared on Sept. 13, at Camp Lee, a training base named for Confederate General Robert E. Lee and located just outside Petersburg. Within two weeks, hundreds of men in the camp had succumbed, the city of Petersburg had been infected, and the state’s health commissioner, Dr. Roy Flannagan, began to close public spaces in the nearby capital, Richmond. All told, more than 16,000 Virginians would eventually die.

Meanwhile, the Normal’s students prepared to return to Harrisonburg. The segregated, single-sex institution drew mostly rural or middle-class urban women who needed and wanted to work for a living. Opportunities for formal education and for professional work had expanded dramatically for white, Southern women in the Progressive Era, and the war meant that certain occupations, like teaching, nursing, and clerical were in high demand. Aged between 16 and 25, the demographic most affected by the “Spanish influenza,” they were eager for classes to commence. From all across Virginia, including Petersburg and Richmond, they boarded trains and headed west, full of anticipation.

Contagion

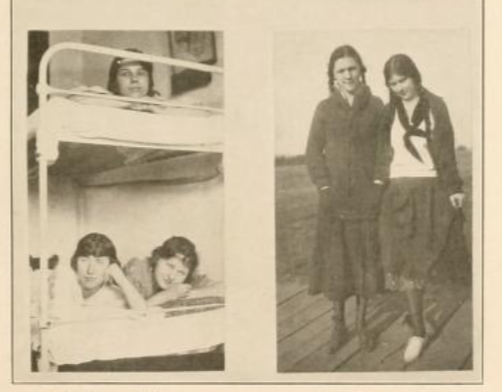

The semester formally commenced that year on September 25. The bluestone dormitories were overcrowded, such was the school’s popularity. Most rooms were doubles outfitted with institutional-grade, easy to clean furniture: iron-frame twin beds and Mission-style oak dressers and desks. Some women shared “triples,” however, and everyone shared busy, common living spaces that modern students would recognize: bathrooms, lounges, dining hall, library. Many of the Normal’s approximately 300 students did not live on campus, however, boarding instead with families or living in special rooming houses and apartments in town. The local paper, the Daily News Record (DNR), reported President Julian Ashby Burruss’s welcome speech at the opening assembly. Wearing their white dresses, which had been required for formal gatherings since the school opened its doors in 1909, the students sat closely together as they listened. At the end, they sang the school songs, Bluestone Hill and Shendo Land, and returned to their rooms to prepare for the start of classes.

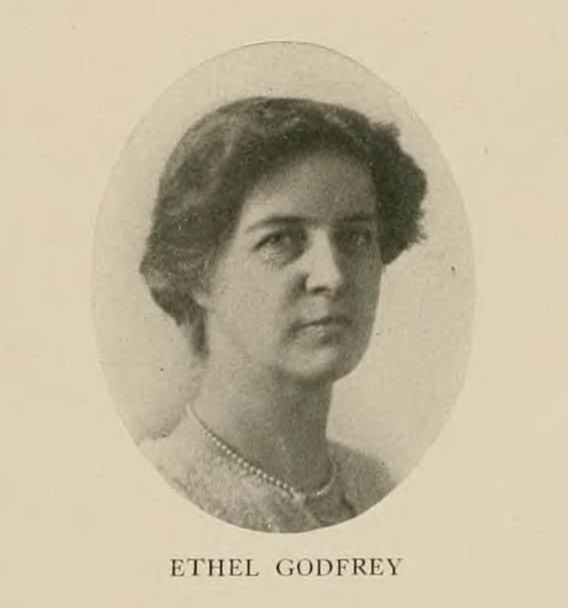

The first influenza patient appeared at the Normal’s infirmary on Sept. 28, just three days after the start of the new semester. Located in Cleveland Cottage, a former house recently named for a beloved faculty member, the infirmary was tiny, just a few rooms, really, and staffed by the school’s nurse, Ethel Godfrey, who also taught basic nursing classes and lived in the cottage. By the end of the next week, so many students had the flu that President Burruss approved the transformation of a dormitory, now called Jackson Hall, into an emergency infirmary.

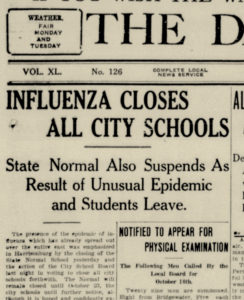

History professor Raymond Dingledine, Jr. wrote in his 1958 campus history, Madison College, that faculty and student volunteers mobilized quickly to tend the sick. Dr. James H. Deyerle, the school’s physician, came to campus regularly. Nurse Godfrey soon contracted the flu and took to her bed. Burruss requested from the state additional nurses, who arrived by train and took over management of the facilities, still staffed by Normal volunteers. Then Burruss fell ill and confined himself to his bedroom in Hillcrest House; he appointed Dr. James Johnston, a chemistry professor, as acting president, but Burruss was not so incapacitated as to lose his authority. By October 6, in consultation with Johnston, Dr. Deyerle, and other administrators, he approved closing the school. The DNR reported that all students and faculty whom Deyerle and the nurses deemed “well” or “sufficiently recovered” were sent home for the duration.

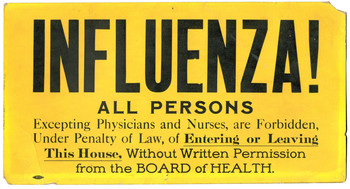

During the closure, the death toll locally and in Virginia continued to mount. Besides schools, the state Board of Health closed public establishments, forbade church services, and promoted a kind of social distancing. Modern scholars argue that government agencies generally downplayed the severity of the actual epidemic to retain morale and avoid panic during war time. I don’t see much evidence of that, actually. Harrisonburg and Richmond papers both show a constant stream of small and large influenza notices, although they are disbursed amidst headlines and articles about troop movements, Liberty Loan campaigns, and President Woodrow Wilson’s early peace negotiations. (Wilson, born in nearby Staunton, VA, was a popular figure locally, and the Normal later named the campus’s largest, most impressive structure Wilson Hall in his honor.) By late October, the epidemic seemed to be winding down, and business interests pressured the government to let them reopen. After an intense debate, state medical officials reluctantly agreed to lift the ban on public gatherings effective Nov. 6.

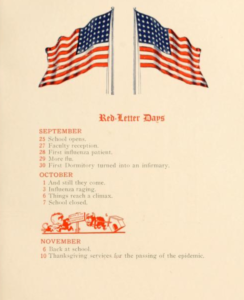

The Normal reopened on Wednesday, November 6, later marked as a Red Letter day in the school yearbook. Apparently, the “entire student body returned” on time, except for a few “who wrote or telegraphed to say they were delayed” and would arrive within the week. The always pious Burruss held a special “thanksgiving” service, likely in the auditorium in Harrison Hall, and asked the women students to avoid downtown, since so many cases of influenza remained. Many popular Harrisonburg establishments had already reopened, including the New Virginia Theater, B. Ney’s fashionable clothing store, and the soda fountain. Despite Burruss’s quarantine, the DNR reporter must have paid a call, however, because he observed that, “there was a marked cheerfulness and eagerness on the faces of everyone” on campus. When Armistice was announced on November 11, the campus had even more reason to celebrate.

Impact

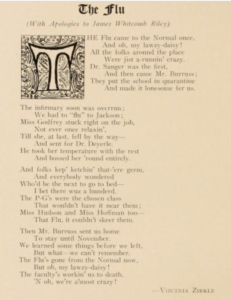

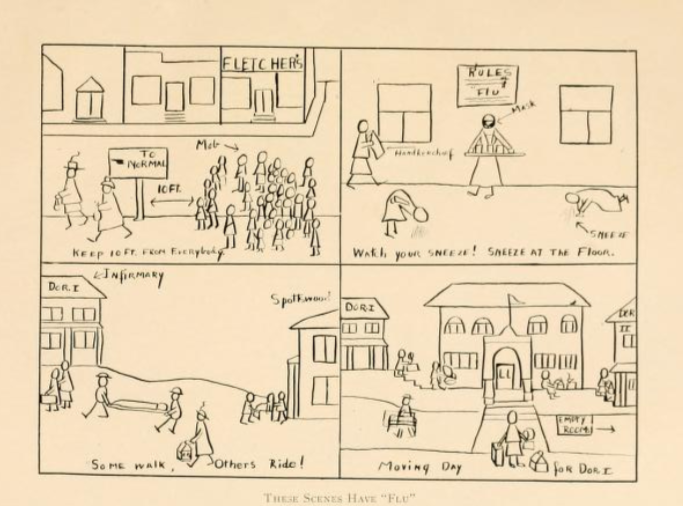

The closure of the Normal and the pandemic, broadly, had a profound impact on the campus community, but it’s hard to tease out the repercussions from available sources. The 1919 School Ma’am offers important, preliminary insights. A poem, “The Flu,” written by student Virginia Zirkle, offers a lighthearted account. It parodies a poem written to commemorate the day when Harrisonburg received news in 1908 that the city would host a new state normal: “The flu came to the Normal once, and Oh, my lawzy-daisy; all the folks around the place, were jist a-runnin’ crazy.” Every aspect of daily life was affected. A carefully-drawn cartoon suggests strong parallels to today’s COVID-19 pandemic: There’s a nurse wearing a “mask”, and captions saying “Keep 10 ft from everybody;” “Watch your sneeze! Sneeze at the floor;” “Some walk, others ride [body in a stretcher].” I see a grim sort of gallow’s humor at play here.

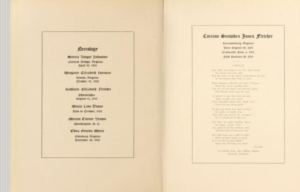

Dr. Dingledine, looking backwards from 1958, celebrates the fact that “not a single life had been lost.” But that isn’t entirely accurate. The yearbook has multiple memorial pages, titled “Necrology” and bordered in black, following mourning customs of the day. Nancy Brown, apparently a member of the senior class, died at home, as did multiple alumnae. Although the pandemic mortality rates for Virginia in fall 1918 (9,685) were modest compared to other states’, such as New York (44,545) and Pennsylvania (61,510), most of the students undoubtedly knew personally someone who died or survived the pandemic. Moreover, there was second wave of influenza that peaked in December and lasted into February 1919. When these figures are added into the 1918 totals, the pandemic’s impact soars.

The Normal would never be exactly the same again. As the DNR noted on Nov. 4, 1918, “Radical Changes in Education” were underway in Virginia, especially for white women. The scarcity in some fields, like teaching and clerical work, reflected the war, certainly, but the pandemic pointed to shortages of public health professionals. One of the Normal’s alumnae, Julia McCorkle, a US Army Corps nurse who served in the European theater, made a strong impression when she addressed the student body. So did Mrs. Vera Jones, the nurse sent to supplement Ethel Godfrey in October. Once the Normal reopened, Jones shifted to managing the local Red Cross chapter’s efforts, and she submitted a sobering report to the Harrisonburg city council in November. City streets without sewers; domestic structures without water on premises; overcrowded, poorly ventilated houses; and substandard sanitation–these conditions, which had fostered the rapid spread of the flu, needed to be addressed as a matter of public health and safety in the future. Members of the graduating class of 1919 were the first women to receive bachelor’s degrees in teaching, approved in 1916. In the 1924, the State Normal School became the State Teachers College, offering expanded programs and new degrees in other fields like nursing, dietetics, social work, and business. In important ways, then, the pandemic helped plant the seeds for the future Madison College and JMU.

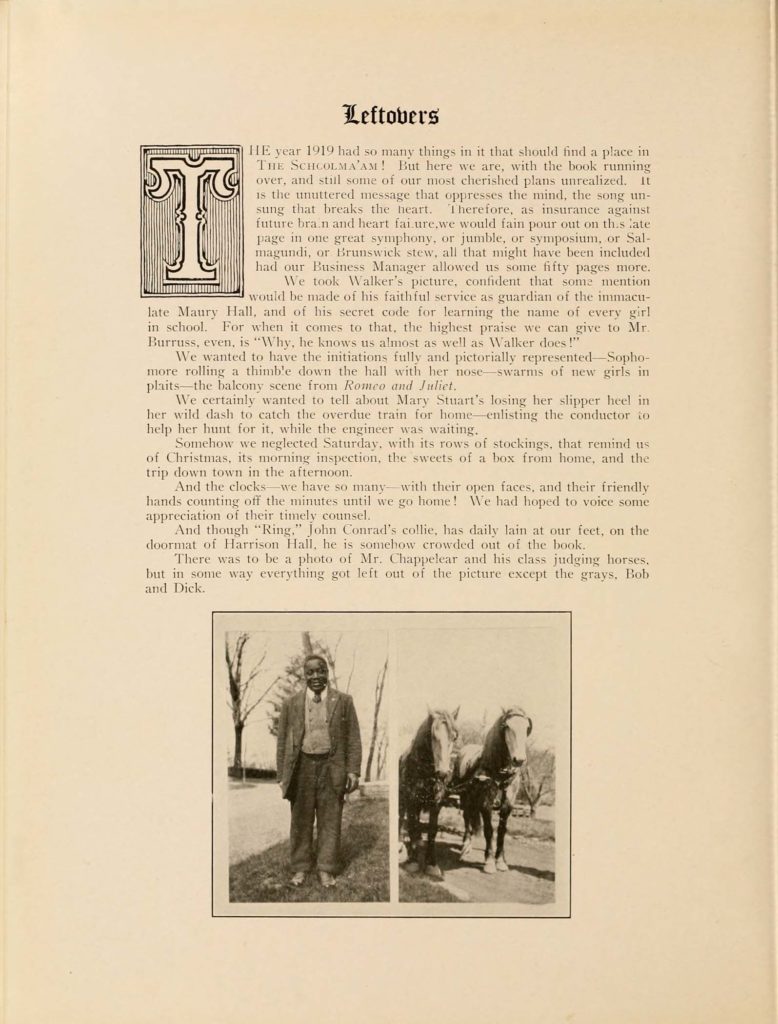

What did not change was the institution’s support for Jim Crow segregation. Buried in the “Leftovers,” a section at the end of the 1919 School Ma’am is a photo of Walker Lee, the Black man employed as janitor in Maury Hall. The accompanying text reads: “We took Walker’s picture, confident that some mention would be made of his faithful services as guardian of the immaculate Maury Hall, and of his secret code for learning the names of every girl in school. For when it comes to that, the highest praise we can give is to Mr. Burruss, even, is “Why, he knows us almost as well as Walker does.” I have found mentions of Lee in another yearbook, as well as in several other early sources. In every white authored source, including his obituary in the Daily News Record, he is offered as a “faithful servant,” a variation of the “faithful slave” trope so characteristic of white Lost Cause narratives. It isn’t clear whether Lee remained on campus during the closure, but the yearbook staff’s impulse to memorialize him suggests that he did. So does a reference in President’s Burruss’s official record of the closure, dated Nov. 4, 1918, which states, “the disease has struck the servants and other employees connected with the boarding department, particularly the laundry, after the students and teachers have been rid of it.” Dozens of white faculty and students remained on site in October 1918, all needing food, heat and hot water, and other essential services of the sort supplied by the Normal’s Black employees. Lee’s mention in the yearbook also reminds us that thousands of African Americans soldiers served in World War I, yet returned home to face anti-black violence and continued oppression. These included six Harrisonburg men, who received a French commendation for their service in the 349th Field Artillery Regiment, a segregated unit. Whether on the battlefront or on the homefront, faithful service did not bring racial equality.

Sources consulted include:

The School Ma’am, 1918-1922

Faculty Minute Book 1915-21

The Daily News Record, Aug. 1918-April 1919

Mortality Statistics, 1918. Dept of Commerce, Bureau of Census (Washington DC: GPO, 1920).

“Richmond, VA,” American Influenza Epidemic of 1918 – 1919: A Digital Encyclopedia. http://www.influenzaarchive.org. April 2020.

Boyer, J. “From the Archives: 1918 Influenza epidemic killed at least 16,000 in Virginia,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 16, 2020.

Caelleigh, A. S. The Influenza Pandemic in Virginia (1918–1919). (2019, April 22). In Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved from http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Virginia_The_Influenza_Pandemic_in_1918-1919.