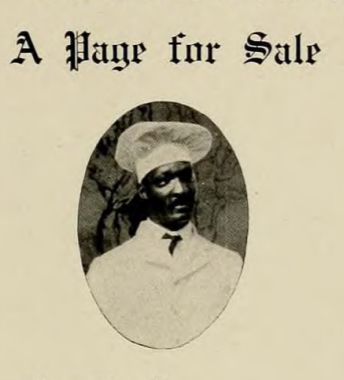

Page Mitchell was one of the most significant employees at the State Normal and Industrial School for Women, for he managed the kitchen that provided three meals a day to hundreds of white students and faculty. Hired as the school’s cook, he is shown in a 1914 image, at left, in chef’s whites. Like Walker Lee and the handful of other African Americans that worked on this campus in the early 20th century, Mitchell contributed to the school’s success, however, little information about him survives in school sources. In this post, I’ll piece together what I have learned about his work so far.

First, Mitchell seems to have been among the group of what President Burruss called “the servants” that he hired just before classes commenced in September 1909. Census schedules and a 1902 voter registration list put Mitchell’s birth year as 1874 or 1875, so he was about 33 years old when he began working at the Normal school. At that time, he had a house on Mt. Crawford Avenue in Bridgewater, about nine miles south of Harrisonburg, where he lived with his wife, Bessie, and two young children, Claude and Calla. Like the school janitor, Walker Lee, however, he probably resided on campus during the week in the “four-room, frame cottage” that Burruss had built “for the colored employees of the school” in 1910. Somehow, Mitchell had acquired skills in food preparation at scale. There is a long history of Black men serving as cooks, of course, and it’s hard to imagine that the hyper-competent Burruss would have hired for an institution of the Normal’s projected size a person without relevant work experience. Being a professional cook put Mitchell in a special category at a time when the segmented labor market denied Black men access to most skilled occupations. Undoubtedly proud of his chef’s whites, by 1927 Mitchell also served as “counselor” and “advisor” to the Blue Circle Club, a Harrisonburg civic organization that included “all the cooks of the city” and hosted “social and athletic events for the betterment of the colored race,” especially an annual banquet for the entire Black community. [Census records; List of voters; Richmond Planet; Celebrating Simms]

Nevertheless, the school’s kitchen and its adjacent dining room were technically the responsibility of a white member of the faculty, Frances Sale. [Dingledine, 40] There were two reasons why Mitchell lacked control over his own workplace: one, the racism that denied Black people authority; and two, the new emphasis on scientific food preparation that dominated this period and led to new curricula with names like “domestic science,” “home science” “domestic economy,” and “household arts.” [Perfection Salad, 4] In keeping with its innovative “laboratory” approach to teacher training, which placed students in actual classrooms with master teachers, the school placed industrial arts students in corollary sites for cooking, nutrition, and household management. Sale, who had a special diploma in domestic science from the nationally renown Teacher’s College at Columbia, had the requisite credentials both to teach the new curriculum in cooking, sewing, and other household arts and manage the relevant practicum spaces. Importantly, these practicum spaces included not only a dedicated cooking laboratory in Science Hall (later Maury Science Hall), but the kitchen, storage area, and dining room that occupied the west end of the basement of Dormitory No. 1 (later Burruss Hall, then Jackson Hall). Raymond Dingledine, a faculty colleague who knew Sale, claimed that she had “an efficient and watchful eye,” which referenced her role in ensuring that nothing was wasted or went missing. Although he recognized “Page the agreeable and able chef” in passing, he said it was Mrs. Roderick Brooke, the matron in charge of Dormitory 1, who initially planned the menus and bought the food. [Dingledine, 40] So what, then, did Mitchell do?

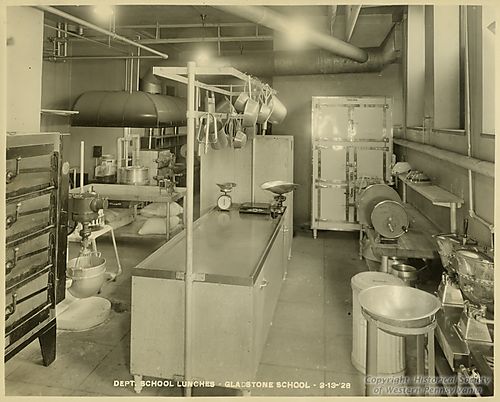

Mitchell managed the day to day operations of food preparation and service, since Sale’s substantial teaching duties meant she could not have been physically present in the kitchen. Consider that breakfast began promptly at 7:45 am and lasted only until classes commenced at 8:30; lunch (called dinner) extended from 12:25 until classes resumed at 1:30; and then supper occurred from 6:00 to 7:00. By the end of the second quarter in May 1910, there were 64 students living on site and 143 who boarded elsewhere but took their mid-day meal on campus. Burruss and the faculty also ate in the dining room. By 1915, 138 students lived on campus, and the number continued to rise every decade. Student-authored sources make clear that all three mealtimes were rushed and crowded for them, so we can assume that Mitchell was especially busy behind the scenes. The logic of Jim Crow tells me there had to have been additional cooks as well as a dishwasher or two. Burruss told the Board of Trustees in February 1911 that six employees lived in the janitor’s quarters. Following Dingledine, Danielle Torisky emphasized in her detailed 2006 study of dining services how white women students enrolled in the Household Arts program (later Home Economics) provided essential supplemental labor as waitresses, yet she erased Mitchell and the Black presence. [Torisky] Similarly, I haven’t found a photograph of the Normal’s kitchen yet, but based on descriptions I have seen of the equipment and furnishings Burruss ordered for other spaces, including the laundry and cooking lab, I think it must have been the most modern, sanitary facility possible. It undoubtedly had elements in common with the school kitchen at the Gladstone school, shown above, which also occupied a basement. But Mitchell’s domain was far too small for the population.

In November 1916, Mitchell moved into a much larger kitchen that occupied the top floor of the annex attached to the new Student Services Building (later called Harrison Hall). The school’s secretary-auditor visited the site several times saying, “I went to the kitchen and watched the manner of serving dinner in the new quarters and was much pleased to see how quickly and efficiently the meal was served and the apparent convenience afforded by the arrangement of the kitchen and serving room.” [quoted in Torisky, 9] Though he, too, intentionally erases the Black staff, the speedy delivery he valued clearly rested on the skilled acumen of Mitchell and his team.

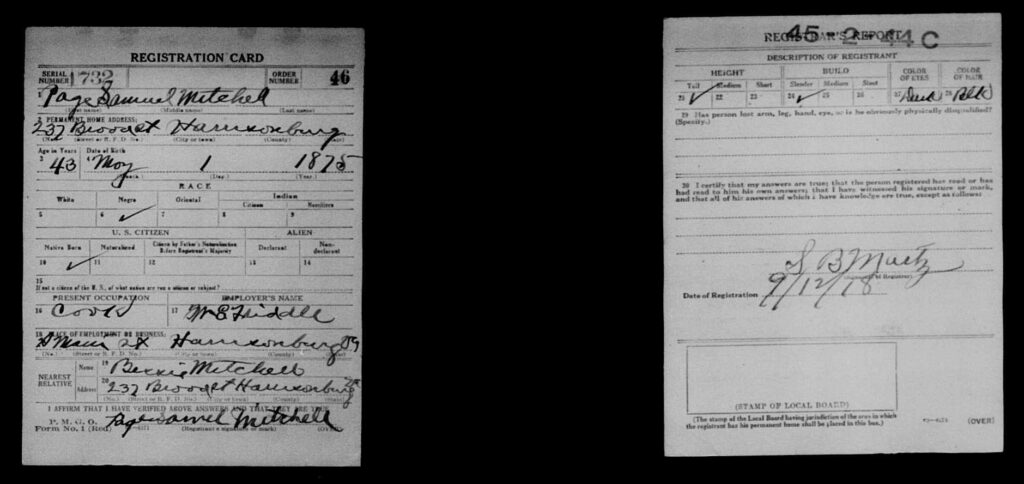

In September 1918, Mitchell completed paperwork required for military service. He reported that he was employed as a cook at W. S. Friddle’s restaurant; why he left the Normal isn’t yet known. The document tells us he was “tall” and “slender” and lived at 237 N. Broad Street, but that’s all. Located on Court Square, Friddle’s was a popular whites-only eatery, one with a long lunch counter that Normal students especially liked to visit on the weekends. Perhaps he received better pay or better hours or more autonomy there. Certainly, the working conditions on campus remained challenging.

Interior photos of the new dining hall show a spacious, light-filled room that extended the full length of the building’s second floor; this room, however, as well as the adjacent kitchen and food storage areas, were still inadequate. Due to World War I, state funds for the services building were first cut, then suspended. According to a January 1919 report, it had “no regular baking equipment at present, necessitating large purchases from city bakers–[and] no cold storage facilities except small refrigerator in basement, necessitating buying in small quantities, sometimes causing spoilage of perishables.” The building also suffered regular heating and plumbing problems caused by the inadequate capacity of the new steam plant installed in the annex’s ground floor. Who replaced Mitchell is unknown, but Burruss reported that these conditions made “kitchen help difficult to secure.” The labor shortage also reflected the fact that numerous kitchen and laundry employees had fallen victim to the Spanish Flu pandemic that year. [Torisky, 10-11]

In the postwar period, as economic opportunities for women expanded, the Household Arts program grew considerably. Frances Sale left for a new position in Mississippi in 1919. Her successor, Pearl Moody, had been hired along with five other program faculty in the 1910s; Moody taught courses in cooking and sewing and supervised the school’s practice house, but as head of the department, she oversaw the school’s dietitian, Hannah Corbett, who assumed charge of the dining hall and its many student waitresses. [Torisky, 9]

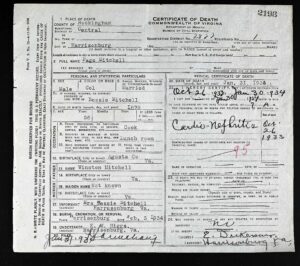

A website called Celebrating Simms offers useful context for Mitchell’s life by interpreting aspects of Harrisonburg’s Black community in the early 20th Century. There were multiple Black-owned businesses in Harrisonburg, for example, but Mitchell continued to work at Friddle’s. Census schedules confirm that many Black men (and some women) labored as cooks in Harrisonburg’s hotels and restaurants. Although a wage earner, 1920 census records state that Mitchell owned his own home, a substantial two-story structure on a sizable lot, and he and Bessie had a boarder, Bertha M. Randall, “supervisor, colored schools.” By 1930, census takers recorded the value of Mitchell’s property as $2000, a respectable sum. Unfortunately, he did not live much beyond that date. Suffering from some form of kidney disease, he sought treatment from Dr. Eugene Dickerson starting in October 1932 and died of “cardio-nephritis” in January 1934. He was only 56. [Census; death certificate]

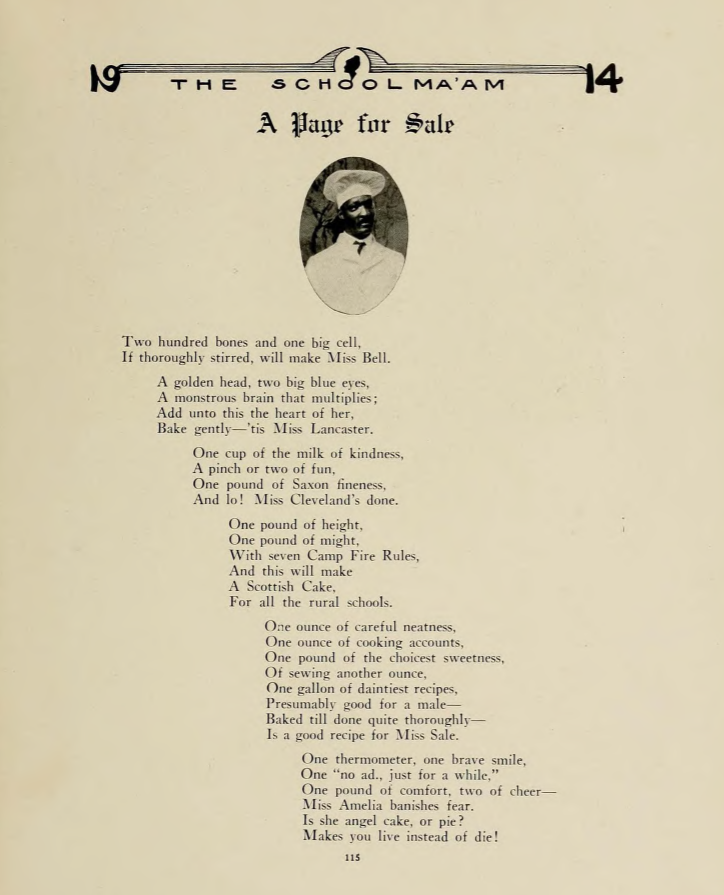

Mitchell was a highly-regarded and highly visible presence on campus, however, like Walker Lee, he clearly occupied a subordinate role. In white-authored sources, he is known according to the Jim Crow customs of the period only by his first name, “Page,” without an honorific or last name. More telling, in 1914, he appeared in a poem and in a skit, both of which reveal white students’ attitude toward Black employees. “A Page for Sale,” for example, features his name in the title and a photo of Mitchell in his chef’s whites, but the verses do not mention him at all. Instead, the title and photo together operate as an inside joke referencing simultaneously the page of the yearbook dedicated to Sale and the Black cook who faithfully serves her. In this way, I think the poem demeans Mitchell by linking him to racist Jim Crow caricatures like Rastus, the toque-wearing chef associated with Cream of Wheat. Read a different way, as an advertisement offering “Page” as a person “for sale,” the poem reflects white students’ nostalgia for the Old South and makes light of the brutality of slavery.

The skit, titled “A Mock Faculty Meeting,” demeans him, too. In it, Mitchell is called forth by the “faculty” to testify about a alleged gum chewing incident. He is described as “one of the most reliable people in the institution,” and a man whose “mother cooked for [Miss Cleveland’s] aunt in Fluvanna County.” These statements position him as a happy, “faithful” servant of the Old South type. When the student cast as Burruss asks him if “one of the ladies at Table 11 uses gum,” a prohibited act, “Page” doffs his chef’s cap per stage directions, and says, “a concatenation of concurrent circumstances conduces to that opinion on my part, sir.” As the interrogation continues, “Page” reveals that he found “an agglutinous [sic] mass attached to the base of the chinaware” several times, but couldn’t say if it was the same brand because “in short, I, uh, uh ,uh, didn’t taste it every time.” Here, the alliteration and greatly affected vocabulary evoke the minstrel character, Zip Coon, an urban dandy whose buffoonish attempts to mimic white speech, dress, and manners undercut notions of racial equality. I can’t tell if the skit was performed, but it seems possible. The full cast was listed by name, except for Mitchell, Walker Lee, and Miss Lyons, the three staff who had speaking parts. Did Mitchell play himself? It seems unlikely given what else is known about him.

Consider how Mitchell appears in February 1930, in a short piece submitted to the Richmond Planet, the state’s leading Black paper, about the Blue Circle Club’s annual “banquet.” Noting that “every chef cook in the city is a member of the organization,” it described the abundant food offered, and noted that “P. S. Mitchell, counselor and advisor, spoke very forcefully on many important issues.” Although we don’t know what he said, Mitchell was important enough a figure to merit that sentence. Further, the paragraph went on to link his remarks ideologically to those of the club president, Percy R. Wells, who “sought to awaken” the audience to the fact that “the doors of opportunity are slowly closing on us and something must be done to rectify the situation.” In particular, Wells mentioned a pending barber shop bill and the “annual [racial] integrity bill,” both of which threatened Harrisonburg’s Black community, and he recommended the ballot and “secret organizations” as its best assets in resisting these measures. [Planet, Feb. 1, 1930] Though brief, these mentions coupled with his leadership role in the Blue Circle Club itself, strongly suggest Mitchell’s activism in support of equality. Such a man would probably not play the buffoonish role white students devised for him.

And this is why I think it’s important to recognize his contributions. As head chef or head cook, he was an essential employee whose expertise made the whites-only school for women successful, despite efforts to ignore or diminish his status. More than that, he also labored to secure the “betterment of the colored race” through his community activity. No doubt more facts about his life are available from public records, as well as stories from his descendants that could flesh out this inadequate biography. In the meantime, I will continue searching through various sources, hoping as I always do to find just a few more crumbs.

Sources include:

1900, 1910, 1920, 1930 US census, population schedules; WWI Registration Card; Death certificate.

Various primary sources from Special Collections: School Ma’ams, Bulletins, official reports, images, etc.

Chappelear, George. “Buildings and Grounds.” Virginia Teacher, 1931.

Gold, David and Catherine L. Hobbs. Educating the New Southern Woman: Speech, Writing and Race at the Public Women’s Colleges, 1884-1945.

Shapiro, Laura. Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century.

Torisky, Danielle. “History of Dining Services at JMU.”

Thanks to Tiffany Cole for sharing Mitchell’s death certificate and registration card.